Nagmaneho Siya ng 25 MPH, Nakakita ng Butil—At Natagpuan ang Babaeng Na-miss ng Lahat

Bahagi 1 — Ang Butil sa Liwanag ng Araw

Nakita ito ni Caleb bago niya malaman kung ano ang nakikita niya—isang munting flash sa mainit na bato, isang turquoise na butil na nahuhuli ng nine am sun. Limang flight sa paghahanap ang naka-skim sa kanyon na ito. Dose-dosenang mga trak ang dumaan. Ngunit sa dalawampu’t limang milya bawat oras, tumigil ang matandang mata ng isang biker.

Siya downshifted, graba ticking ang chrome, at luwag ang kanyang Harley sa mabuhangin labi ng pullout. Ang GPS ay namatay dalawang switchbacks nakaraan. Ang mapa sa kanyang telepono ay isang kulay abong kubrekama. “Well, Trace,” ungol niya, gamit ang pangalan ng trail na hindi niya binabanggit sa loob ng maraming taon, “maling daan, tamang umaga.”

Ang butil ay nakahiga sa isang pasamano kung saan ang balikat ay nabasag sa apatnapu’t talampakang patak. Hindi ito nag-iisa. Sa tabi nito, ang alikabok sa bato ay nagsuot ng maliliit na buwan kung saan ang mga daliri ay pinindot at nadulas. May mga bahid na parang batang sinubukang umakyat, nabigo, sinubukan muli. Naramdaman ni Caleb ang pagbabago ng hangin sa loob ng kanyang dibdib, tulad noong araw na nahati at nawala ang lahat sa kanyang buhay.

Pinatay niya ang makina, hinayaan niyang bumalik ang tahimik na baha—sumirit ang damo, malayong batis, lawin sa isang lugar na hindi nakikita. Sinuri niya ang anggulo ng slope. Masyadong matarik para matisod. Hindi sapat na matarik upang idahilan ang pagtalikod.

Nagrereklamo ang kanyang mga tuhod habang siya ay lumuhod. Animnapu’t isang taong gulang, dating lineworker, dalawang vertebrae na lumalamig sa panahon, at isang pangako na hindi niya tinupad sa iba kundi sa kanyang sarili: minsan sa isang taon, sa isang tiyak na linggo, sumakay sa mataas na bansa at makinig. Hinubad niya ang isang coil ng tie-down webbing mula sa saddlebag, inikot ito sa paligid ng juniper stump, sinubukan ito ng dalawang beses, at nagsimulang pababa.

Bumigay ang alikabok sa ilalim ng kanyang bota. Ang isang natanggal na maliit na bato ay dumadagundong magpakailanman. “Mabagal at parisukat,” huminga siya, tinig ang kanyang mga kamay. Labinlimang talampakan. Dalawampu. tatlumpu. Ang butil ay humantong sa kanyang mga mata. Ngayon ang isang piraso ng purple na nylon na nakasabit sa scrub ay nagpabagsak sa kanyang tiyan. Isang backpack, maliit, scuffed, may sirang zipper pull na hugis bituin.

“Hello?” Hindi siya sumigaw. Kakaiba ang hiniwang tunog sa mga kanyon. “Hey there. I’m Caleb. I’m here.”

Natagpuan niya siya sa isang bulsa na may lilim na nakaduyan ng bato, na para bang ginawa ng lupa ang isang malambot na lugar para sa isang matigas na bagay. Isang batang babae, marahil siyam, ang pisngi ay may bahid ng alikabok, ang buhok na gusot ng mga pine needle, nakabalot ng jacket na masyadong malaki para sa kanya—ang laki ng pang-adulto, awkwardly naka-zip sa kanyang baba. Ang isang braso ay nakahiga sa kanyang tagiliran, ngunit ang kanyang dibdib ay tumaas at bumagsak.

Napaluhod si Caleb. “Hoy, bata,” sabi niya, tinig ang paraan ng iyong pagsasalita sa paligid ng isang natutulog na ibon. Dinampi niya ang dalawang daliri sa leeg niya. Pulse. Manipis pero nandiyan. Bahagyang amoy ng sabon at ulan ang dyaket at isang taong nag-aalaga nang husto upang isukbit ito sa kanya ng mahigpit.

Nanginginig ang talukap niya. “Nanay?” Ito ay hangin, hindi tunog.

“Hindi ako ang iyong ina,” sabi ni Caleb, “ngunit ilalabas kita rito.”

Bumukas ang kanyang mga mata—kayumanggi, masilaw, mabangis. “Pulis ka ba?”

“Hindi po ma’am.” Napangiti siya gamit ang gilid ng bibig. “Isa lang akong biker na naligaw.”

Napakurap-kurap siya doon, na para bang may kung saan sa isip niya ang mga salita. “Sabi ni nanay kung hindi ko makita ang langit, hintayin mo ang taong nakatingin sa mata.”

“Iyan ay isang matalinong ina.” Sinuri niya ang kanyang binti, maingat na mga kamay, pagkatapos ay ang braso na hinawakan niya malapit. Walang bone showing. Pamamaga. Pinunit niya ang isang strip mula sa kanyang T-shirt at gumawa ng malambot na lambanog. “Anong pangalan mo?”

“Maya.” Ang mga pantig ay hugis ng hininga.

“Hi, Maya. I’m Caleb. Aakyat na kami.” Pinadulas niya ang webbing sa kanilang dalawa, isang sinturon na nangako. “Hindi ito magiging mabilis, ngunit ito ay magiging ligtas.”

Ang pag-akyat ay nagnakaw ng oras. Sampung talampakan, pahinga. Lima pa, huminga ka. Nasusunog ang kanyang mga hita. Naalala ng kanyang mga palad ang mainit na kagat ng alambre mula sa tag-araw na nakasabit sa pagitan ng mga poste. Sa itaas niya, kumindat ang Harley sa araw na parang parola. Sa ibaba, pigil hininga ang canyon.

“Sabihin mo sa akin ang isang bagay na gusto mo,” sabi niya nang madulas ang pader sa pawis.

“Cereal that crackles,” bulong niya. “At kapag ang aso sa kalye ay bumahing.”

“Iyan ay isang magandang listahan.” Sabay tawa niya, maikli, ang tunog na ikinagulat nilang dalawa. “Magdagdag ng ‘sariwang hangin sa tuktok ng burol.’ Malapit na tayo.”

Sa gilid, gumulong siya sa graba at hinila siya kasama niya. Para sa isang beat nakahiga siya na nakatitig sa langit, nakatikim ng metal at alikabok at kaginhawahan. Pagkatapos ay hinubad niya ang kanyang leather jacket at ibinalot ito kay Maya, na parang cocoon. “Sapat na ang init mo?”

“Ito ay parang ligtas,” bulong niya, ang kanyang mukha ay kalahating nawawala sa loob ng kwelyo.

“Walang mga bar,” sabi niya, tiningnan ang kanyang telepono. Ang kalsada ay isang laso na walang sasakyan sa magkabilang direksyon. “Ang pinakamalapit na bayan ay dalawampung milya.” Ibinagsak niya ang isang paa sa ibabaw ng bisikleta, pinaupo siya sa harap niya, nakayakap sa jacket, ang magandang braso nito sa kanyang bisig. “Nakasakay ka na ba dati?”

Umiling siya, isang fraction.

“Ito ay parang lumilipad nang hindi umaalis sa lupa. Kumapit ka ng mahigpit. Ako ang gagawa ng iba.” Pinaandar niya ang makina, at ang puso ng makina ay naging pangalawang tibok ng puso. Magkasama nilang kinuha ang unang liko tulad ng isang pangako, niyakap ang loob, ang mundo ay lumalawak sa bawat bakuran.

Ang gasolinahan sa labas ng County Road 14 ay may kupas na karatula at isang kampana na tumunog nang bumukas ang pinto. Binuhat ni Caleb si Maya. Ang clerk—bata, pekas, isang baseball cap na may sun-bleached logo—ay bumaba ng isang roll ng quarters nang makita niya ang dumi at lambanog.

“Tumawag sa 911,” sabi ni Caleb, huminga nang matatag ngayon na maaari na. “Maya ang pangalan niya. Kailangan niya ng tulong.”

Kinapa ng bata ang telepono, pagkatapos ay kinuha ito, tumataas ang boses habang nagre-relay ng mga salita tulad ng mga coordinate at “dehydrated” at “conscious.”

The sirens came first as a far hum, then as heat. EMTs shouldered through with a calm that made the room bigger. Oxygen, questions, hands that knew what to do. A patrol unit rolled in behind them, lights turning the sun into pulse.

A sergeant stepped close, kind eyes older than his face. “Sir? You brought her in?”

“Yes,” Caleb said. “Found her off the ridge. There’s—there might be a car down there. I didn’t see it, but—”

“We’ll send a team.” The sergeant glanced at the jacket wrapped around Maya, the way her fingers pinched the cuff like an anchor. He lowered his voice. “Mr. Walker, I need you to come with us to answer a few questions. It’s routine, but—” He checked something on his phone, jaw tightening a degree. “You also match a description connected to an earlier call from the highway. We’re going to need to clear that up.”

Caleb felt the room tilt a hair, the way it does when an elevator starts moving and your body learns late.

Maya’s eyes found his. She pulled the jacket closer, as if it could make a circle no one else could cross. Her voice was small but certain. “Please don’t take his jacket.”

Part 2 — Routine, Until It Isn’t

“Please don’t take his jacket,” Maya said, small voice, steady aim.

The sergeant glanced at the EMT who was fitting a blood pressure cuff around her narrow arm. “We won’t,” he said gently. “It’s okay to keep it on.” He nodded to Caleb. “Sir, ride with us or follow behind. Just some questions.”

They eased Maya onto a gurney, wheels chirping over the tile. As the ambulance doors closed, she found Caleb’s eyes again and lifted two fingers in a tiny salute, the kind kids invent to mean everything. The doors clapped shut. The siren rose and carried her away.

Caleb exhaled for the first time in what felt like an hour. The gas station bell dinged once in the hush that followed, like an afterthought from a calmer world.

“Mr. Walker?” The sergeant—badge read S. Ortega—gestured to his cruiser. “We’ll be quick.”

The questioning room at the substation wasn’t a cliché—no bare bulb, no metal chair—just a windowless office with a humming vent and two paper cups of water. Ortega set a small audio recorder on the desk and pressed a red button. “State your name, age, where you found the child, what you observed. Take your time.”

Caleb kept his answers clean. Turquoise bead. Purple backpack. Forty-foot drop. Tie-down strap. Pulse like a small drum. Jacket. The climb. Twenty miles. County Road 14. He gave them the moments in order, the way he used to fill out incident logs after a storm knocked out half a county’s power: plain and complete.

Ortega listened without interrupting, eyes steady, pen quiet. When Caleb finished, the sergeant flipped open a folder. “About the earlier call,” he said. “A motorist reported seeing a male on a motorcycle stopped near the shoulder around Mile Marker 88—a few miles from where the family’s car likely left the road. The caller thought he saw the biker look into vehicles.”

Caleb frowned. “I wasn’t anywhere near eighty-eight. My GPS died before the pass. I took a cutoff to the old service road. Haven’t been on the highway since sunrise.”

Ortega slid over a still frame—grainy highway camera, a dot of a bike, a dark shape. “We pulled this. Helmet looks matte black. Jacket’s got reflective piping on the shoulders.”

Caleb tapped the photo with a calloused finger. “Not me. My lid’s gloss with a sun visor. No piping on the jacket. You can check my gas receipt at mile 102 at 6:14 a.m. I was south of there when this was taken.” He didn’t try to force his voice calm. It either was or it wasn’t.

The sergeant’s mouth twitched—relief, maybe, or just a muscle agreeing with the facts. He clicked his pen shut. “I figured. Routine can sound like accusation. I appreciate you staying steady.”

“Kid needed air more than I needed pride,” Caleb said.

Ortega stopped the recorder. “Search team’s en route to the ridge you described. We’ll update you as soon as we know more.” He stood. “And Mr. Walker—thanks. However the story gets told, it started with you carrying a child up a wall.”

They let him out the side door. Daylight hit like rinse water. He sat on the curb and called no one. There was no one to call. He ran a palm over the grit on his jeans and felt the ghost of a small hand pinch the cuff.

His phone buzzed to life—bars again—and then it didn’t stop. Unknown numbers. A text from an old coworker: You on the news? Another: Is that your bike? Holy smokes, Trace. A local station had already pushed a clip: Biker Brings Missing Girl to Safety. The thumbnail was a still from the gas station camera: Caleb stepping through the door, Maya in his arms, his jacket wrapped around her like a storm cloud.

The story caught speed the way dry grass catches a match. Someone pulled a photo from a missing persons flyer—Maya’s school picture—big front teeth, a cowlick she probably hated. A woman on Facebook claimed she drove County Road 14 daily and always waved to riders; today she’d waved at a man with kind eyes. The gas station clerk posted a cell phone video of the ambulance doors closing and wrote, I’ll never forget her whisper, “It smells like safe.” Ten thousand shares before Caleb could blink. A reply thread argued whether “safe” had a smell. Another thread argued whether it should matter what a rescuer rode.

It wasn’t all clean. A stranger with a flag avatar typed: Convenient he “found” her when the search was called off. Someone else snapped back with a paragraph about topography, outflow winds, and how aircraft miss what a crawling pace and a human gaze find. The internet was doing what the internet does: knitting quilts and throwing stones.

Caleb didn’t answer any of it. He swung a leg over the bike and headed for the hospital two towns over, where they’d taken Maya. The road unwound and rewound, a ribbon tossed and caught again. His hands sat easy on the bars, but his chest hadn’t decided on a rhythm.

He had not walked into a hospital since a night twelve years ago when a hallway had opened like a long throat and swallowed his son. He told himself he would stop at the parking lot and take stock. He told himself a lot of reasonable things that had nothing to do with the moment a girl pinched a jacket cuff like it was the edge of the world.

At the information desk, a volunteer with silver hair and a blue vest looked up. “Can I help you, hon?”

“I’m… I brought in a child,” he said. “From the canyon. Maya.” Saying her name steadied him. “They took her here.”

“Oh.” The volunteer’s face lit with a private relief that made Caleb’s eyes burn. “They did. She’s in the pediatric wing. They’ll ask you to wait in consultation first.” She slid him a visitor sticker. It felt absurdly like a hall pass from high school. HELLO, MY NAME IS… CALEB.

A woman in scrubs stepped into the waiting room with a clipboard tucked to her side. She was maybe mid-thirties, hair pulled back in a no-nonsense ponytail, eyes that had learned the difference between panic and urgency. “Mr. Walker? I’m Dr. Lila Chen, pediatric psychology.” She offered a hand; her grip was warm and firm. “Maya’s stable—dehydration, a fractured radius, scrapes, you know the drill. She keeps asking if your jacket is staying.”

“It can,” Caleb said. “It should.”

“That’s what I told the nurses.” Lila gestured to a pair of chairs near a fish tank where neon tetras blinked like living commas. “Can we talk about anchors?”

He nodded, not trusting his voice to say he’d anchor a mountainside if asked.

“In trauma,” Lila said, sitting, “we look for what a child’s nervous system tags as safe. It can be a smell, a texture, a sound. The jacket probably smells like cedar and road and… you.” Her smile tilted, just enough to make space for the absurdity. “Maya’s system grabbed that and said, Here. I’m not alone. If you can stand it, a short visit—no hero talk, no promises—could help her land.”

Caleb swallowed against a throat that had gone tight. “I can stand it.”

They washed his hands at a sink that smelled like citrus and felt like a ritual. The pediatric wing door sighed open with a badge swipe. Hallways painted with planets. A paper rocket taped to a doorway. A nurse with sunflower-print clogs humming something that might have been a lullaby slowed down and stretched to fit the grown world.

Maya’s room held a just-woken quiet. She lay propped on pillows, IV taped to the back of her hand, the jacket a dark valley around her shoulders. Her hair had been gently combed; someone had coaxed the pine needles out. TV muted. A stuffed giraffe sat at the foot of the bed like a sentry.

When she saw him, the muscles around her mouth did a thing that wasn’t quite a smile and wasn’t not. “You came back.”

“Said I would,” he answered, stepping in as if the room were sacred ground.

“Did you get in trouble?” she asked, serious in the way certain children are born.

“A little,” he said, because truth can be small and still be true. “They cleared it up.”

She absorbed that, then studied him with the methodical gaze of someone who had learned that details matter. “Your jacket smells like rain on a garage floor,” she said. “And… cinnamon?”

“Could be the gas station donuts.” He pulled up the chair. “Doctor says short visit. That means I ask you one big question and then I sit quiet while you rest.”

“What’s the question?”

“Do you want me to leave the jacket if I have to go before you wake up again?”

She looked down at the collar bunched at her chin, then back up. “It’s mine right now,” she said, a negotiation, not a demand.

“Then it’s yours,” he said.

Lila stood in the doorway, arms folded in that balanced way clinicians keep, witness without intrusion. “We’re coordinating with law enforcement,” she said softly when Caleb stepped back into the hall. “They found a vehicle down the slope. Notifications are… underway.” Her pause wrapped something unspeakable in respect. “There will be press. We’ll try to buffer. If you want off the grid, now’s the moment.”

“I’m already off most of it,” Caleb said. “But I don’t want her to go through this with strangers’ voices only.”

“Then we’ll make a plan. Visits, limits, routines.” Lila scribbled a number on the back of a clinic card. “For what it’s worth, Mr. Walker—people talk about heroes like they wake up wanting the title. Mostly they’re just people who were close enough and didn’t look away.”

He slid the card into his wallet next to a photograph he didn’t take out in public. Two faces there—one frozen at nineteen, one coated in canyon dust and wearing a jacket too big.

Downstairs, he stepped into the afternoon and into a weather system made of cameras. A reporter with perfect hair and a mic he didn’t recognize leaned forward as if proximity could extract a quote. “Sir! Sir, are you the rider who—?”

Caleb held up a hand, not unkind, just done. “A little girl needs quiet,” he said. “If you want a statement, here it is: go slow. You see more.”

By nightfall, his words were on a chyron under drone footage of the ridge. A still of the bead—someone had gone back and photographed it—shimmered between commercials for trucks and toothpaste. A pundit in a studio asked whether amateurs should be part of official searches. A retired firefighter said a thing that made the studio quiet: “Sometimes the difference between found and missed is fifteen miles an hour.”

Caleb turned off the TV in his small apartment and set his helmet on the counter. He washed canyon out of his hands again though it wasn’t there. On the coffee table, his phone lit with a message from an unknown number.

This is Eleanor Brooks. Maya’s grandmother. I’m flying in at dawn. They said you brought her home. Thank you. Please don’t disappear.

Part 3 — The Last Ride You Keep

They held the service in a sunlit room at a community center because the church was booked and because Eleanor said her daughter preferred places where kids didn’t have to whisper. Rows of metal chairs. A long table of paper cups and two coffee urns that clicked and sighed. A poster board with photos stood on an easel: school carnivals, a science fair ribbon, a brown-haired woman with laugh-lines helping a student plant tomatoes in a raised bed.

“Her name is Renee,” Eleanor told Caleb when they met at the hospital doors that morning, voice calm from a lifetime of teaching first graders. “Renee Brooks. She worked as a school counselor. On weekends she took extra shifts with the volunteer ambulance crew.” The older woman’s hand squeezed his, bones delicate and certain. “She prepared Maya for hard things without frightening her. Lists, small bags ready by the door, a song for when you feel alone. That jacket you wrapped her in? She would have approved.”

Maya waited in a wheelchair with a pink cast on her arm and Caleb’s jacket over her shoulders like a cape. Someone had slid a tiny turquoise bead onto a thin ribbon and tied it to the zipper pull. The sergeant, Ortega, had found it on the ledge when the team went back for the car and handed it to Lila with a quiet, “When they’re ready.”

Now Maya pinched it between thumb and forefinger as if testing whether a miracle would hold.

“Morning, partner,” Caleb said.

“Morning,” she said, small smile, eyes the steady kind that asked for the middle of things, not the edges. “We’re saying goodbye today.”

“We are,” he said. It surprised him that the words didn’t wobble. Maybe grief recognized grief and made room.

They rode in the procession behind the simple hearse. No police motorcycles flanking, no chrome spectacle. Just neighbors who had brought casseroles and borrowed jackets, teachers who had set out extra chairs, and a cluster of riders who had seen the news and drifted in one by one because you don’t leave a kid to follow a hearse alone if you can help it. Some rode scooters. One had a sidecar with a dented fender. Helmets nodded like slow metronomes.

Inside, the service moved the way good ones do—held by small kindnesses, not speeches. The principal read a letter from a student whose mom had gotten a job after Renee wrote a reference. A paramedic with a sunburned neck told a four-minute story about roadside calm in a thunderstorm. Lila spoke two sentences about anchors and then didn’t explain the metaphor to death.

Eleanor stood at the lectern, a handkerchief folded precisely the way you fold things to keep them strong. “My daughter taught children how to say hard truths in small pieces,” she said. “So here are my small pieces. We are devastated. We are grateful. We will go on.” She paused. “And we will not let the way a story ended erase the way it was lived.”

Then she looked down at Maya, patted the hand gripping the bead, and said, “My granddaughter would like to ask someone to speak.”

Maya’s chin lifted. “Caleb, please.”

He had told himself he would say no. He had told himself he would not take a microphone into a place where his hands might shake. But the child asked and the room did a quiet thing—people leaned without leaning, like pines catching snow.

He stepped up. The mic was already the right height, a grace so small you only notice it when you need it.

“I didn’t know Renee,” he began, voice rough as gravel and warm as coffee. “But I know the shape of her love because I saw what it left. On a wall of rock, there were little moons where a small hand tried and tried. Up on the rim road, there was a backpack with a star on the zipper. Down in a pocket of shade, there was a child wrapped in a jacket that smelled like rain on a garage floor.” He let the room breathe. “A person who thinks ahead for other people—who teaches a kid to ration snacks and wait where shade holds—who gives up her own warm to keep a child warm—that person is a builder. The last thing she built was time, and her child used it to live.”

He looked at Eleanor, then at Maya. “I carried your girl twenty minutes and it felt like a year. Your daughter carried her for six days without moving an inch. There are lots of words for hero. Today, I think the right one is parent.”

He put the mic back, hands steady enough to surprise him. When he sat, Maya leaned into his shoulder. The bead tapped his knit cuff—tick, tick, a second hand starting up again.

The burial was quiet. A wind moved the grass in polite waves and left the cedar trees alone. Someone from the PTA had made cookies shaped like stars and the caterer’s kid—freckled, gap-toothed—walked the tray around like a sacred duty. Caleb took one he didn’t taste. He couldn’t quite choose between standing far back and standing close, so he stood at the exact place where the two instincts met.

When it was time, Eleanor touched Maya’s hair. “I can ask anything?” the girl said.

“As long as it’s not a pony,” Eleanor whispered, the joke practiced and paper-thin and enough.

Maya turned to Caleb. “Can I… can I ride with you? Just to the gate. To say goodbye with the wind.”

Heads turned. You could hear the thought run the aisle: is that allowed, is that okay, does that… But then a woman from the ambulance crew said, “I’ll walk alongside,” and a teacher said, “I’ll too,” and a man with a stroller stepped forward, and suddenly it wasn’t a question, it was a plan.

Caleb swallowed. “We go slow,” he said. “As slow as the day asks for.”

They set her in front of him the way they had at the gas station, her cast resting like a fragile promise, his arms a guardrail that could flex. The jacket swallowed both of them. He didn’t start the engine until he saw Eleanor nod and until Ortega—standing a respectful distance away—caught his eye and touched two fingers to his temple. Then the bike grumbled awake into a patient idle.

It was not a spectacle and that was the spectacle. No roaring throttle, no chrome parade. Just a line of people—the stroller, the EMT in navy pants, the principal still in his name badge, two teen skateboarders who had taken off their caps, the scooter with the dented fender—moving at walking speed behind a plain car, while a child in a too-big jacket put her hand on a fuel tank and closed her eyes.

At the gate, he clicked the engine off. Wind took over where the motor left off, a soft hush that packed more meaning than sound does.

“Goodbye, Mom,” Maya said, not loud, not brave for show, just true. She touched the bead like a button that could connect two rooms. Eleanor, standing to the side, did the same thing with her handkerchief—one tap against her heart. People who didn’t know where to look looked at the cedar trees and pretended to study birds.

Phones appeared: this is what people do in 2025 when they want to keep something from running away. But the photos that moved later that day didn’t feel like intrusions. They looked like witnesses.

By dusk, one image had stepped out in front of the others: a girl in a leather jacket three sizes too big, chin tucked, cast pink as sunset, perched on a bike at the end of a cemetery lane, a line of neighbors in the background, all in that small posture people take when they mean respect. The caption that stuck came from a parent who’d once sat in Renee’s office: She spent her life walking kids to gates. Today a town walked her daughter there and back.

The clip went where clips go—local stations, then national, then the debate shows where people shape questions with fancy edges. Should children ride in processions? Should communities allow “non-officials” to play roles in official grief? Someone argued that motorbikes at funerals were “performative.” A grandmother in a cardigan called the station, voice shaking with a smile, and said, “Honey, everything about a funeral is performative. Performing love. Performing memory. Performing the promise we’ll look after the ones left.”

Caleb stayed out of all of it. He helped Eleanor carry lilies to the kitchen because lilies leak and make a mess if you don’t. He wiped a ring of coffee off a table without being asked. He held doors for people who didn’t realize doors could still be held. He didn’t try to hold the day. Days do not like to be held.

As the room emptied, a woman with a county badge, khakis, and the kind of tired that reads as competence came over. “Mr. Walker? I’m Dana Ruiz, family services.” She offered a business card printed on stock that had survived a thousand purses. “First—thank you. Second—Maya’s a resilient kid, and we want to keep her world steady while it heals. That means routines. It also means… boundaries.”

Subscribe to Tatticle!

Get updates on the latest posts and more from Tatticle straight to your inbox.

We use your personal data for interest-based advertising, as outlined in our Privacy Notice.

He nodded. “Say what you need to say.”

“You matter to her,” Dana said. “That matters to us. We’ll set up a plan—visit times, check-ins, guardrails—so she doesn’t have to choose between attachment and safety. We can talk details tomorrow when everyone’s slept.”

“Tomorrow is good,” he said.

She hesitated. “One more thing. The press will come in waves. Today they were mostly kind. Tomorrow they will be hungry. If you don’t want the story to eat the people in it, let us help you draw lines.”

He looked across the room. Eleanor and Lila were packing photo boards into a tote. Maya had fallen asleep in a chair, the jacket puddled at her feet, the bead winking like a small planet caught in a pocket of night.

“Lines,” he said softly. “Yes, ma’am. Let’s draw them straight.”

Outside, the riders who had drifted in drifted out the way good help does—without asking for thanks. A teenager on a skateboard paused by Caleb as he secured his helmet. “Sir? Your jacket smells like my granddad’s garage,” he said solemnly, as if offering a diagnosis. “In a good way.”

“It’s been through some weather,” Caleb said.

“Yeah.” The boy looked at the line of cedars, the gate, the sky that was thinking about stars. “Me too.”

Caleb watched the last cars go. The quiet after a funeral is a compound you can taste—part relief, part ache, part hunger for something warm and ordinary. He swung a leg over the bike and sat there a minute, hands on the bars, before heading home.

He took the long way, the slow way, the way with the lookout where you can see a whole town breathing. From up there, porch lights flickered on one by one like a string of beads finding sunlight. He didn’t count them. He just sat until the day softened, then started the engine and went down to where people were, because that’s where the next part would happen, and because tomorrow he had a meeting about boundaries and, maybe, the start of a plan.

Part 4 — Lines You Draw With Care

Dana Ruiz brought paper, not a lecture. In Eleanor’s kitchen the next morning—sun on a bowl of oranges, a radio whispering weather between songs—she laid out a single printed page and a pen.

“Routines,” she said, tapping the header. “They’re how we make a shaky world hold still.”

Eleanor poured coffee into three mismatched mugs. “I taught first grade for thirty-two years,” she said, handing one to Dana, one to Caleb. “You’re speaking my love language.”

Maya sat at the table with her cast propped on a folded dish towel, drawing a motorcycle that looked suspiciously like Caleb’s. She had added stars on the tank and little beads on the mirrors.

“Okay,” Dana said, businesslike, kind. “Ground rules. We want Maya’s life to feel normal. That means school when cleared, counseling with Dr. Chen, consistent bedtime, no interviews, no pressure to be brave for cameras.”

Maya didn’t look up from her drawing. “Agreed,” she said, serious.

Dana smiled. “Anchors. The jacket is an anchor. It stays. We’ll also build a ‘calm kit’: a soft scarf with cedar chips sewn in, a small radio with white noise, and…” She glanced at Caleb. “A keychain, maybe? Something metal from your garage that smells like… well, garage.”

“I’ve got an old wrench that’s too small for anything,” he said. “Smells like old summers.”

“Perfect.” Dana checked a box. “Contact. We’re recommending three short visits a week, scheduled. Phone calls allowed before bedtime if Maya asks. No surprise drop-ins. We’ll reassess in two weeks.”

Eleanor nodded, the exact pace of a metronome. “I appreciate the boundaries.”

Maya finally looked up. “I want Sundays,” she said. “For rides.”

“Walks for now,” Eleanor said gently. “Wheelchair or park bench until your arm says motorcycle again.”

Maya considered, then amended her picture: she drew the bike smaller, the stars bigger. “Then Sundays for sitting and looking at roads,” she said. “We can go slow without moving.”

“That’s a good line,” Caleb said, and didn’t realize it until the room echoed it back as a smile.

They tacked the routine sheet to the fridge with a magnet shaped like a tomato. Maya added a tiny drawing of a bead in the corner, as if to sign the contract.

Dr. Chen arrived with a canvas tote that could have been for a beach if not for how professionally it was packed. “Coloring pencils.” She set them out. “Breathing cards.” She fanned laminated squares with pictures of waves and trees. “And a story: the day a jacket learned to be a bridge.” She looked at Caleb. “We’re borrowing your smell for good.”

“If my garage can help, it owes me one,” he said, rubbing a grease shadow on his thumb that wasn’t really there. He caught the way Eleanor watched—the measuring look of an adult who has survived long enough to trust carefully—and inclined his head to it.

The afternoon moved like a well-made clock. A neighbor dropped off soup. Eleanor’s church friend texted, We can carpool to school when it’s time. A boy from down the block knocked to ask if Maya wanted to see his origami phoenix; she did, and he stood in the doorway making it flap while she laughed like laughing was a new room she had just discovered.

If you’ve ever been part of a small mercy, you know its sound: chairs scooting, doors clicking, the quiet tick of a pen on a checklist. All of that lived in the house that day.

Caleb learned the house like you learn a road—where the pantry door sticks, which stair complains, where Eleanor keeps the good tape. He sat with Maya while she traced stars. “If you tilt a star it looks like it’s moving,” she said, tilting one until it leaned. “Like it’s going slow but still getting somewhere.”

“That’s how I do it,” he said.

The world outside the kitchen kept moving too. A columnist in the Post wrote about “the ordinary holiness of slowness,” quoting a retired firefighter who said, “Fifteen miles an hour can be the difference between found and missed.” A risk manager in a neat suit went on TV and said volunteers were liabilities. A search-and-rescue captain with weather-beaten cheeks countered: “Liability is leaving eyes off the ground.”

Caleb didn’t have a TV on in his apartment that night. He had a list. He wrote “wrench keychain” at the top and “ask Dana about school pickup rules” under it. He added “call lineworker buddy about radio repeaters”—because a thought had been growing in him since the canyon: not a rebellion against drones and tech, just a lane where people could be the missing tool.

The next visit was Wednesday at four. The sky was the blue of new jeans. Caleb parked two houses down to keep things quiet. Inside, Maya had constructed a “bike school” on the living room rug: couch cushions as cones, a stripe of masking tape as a finish line, the stuffed giraffe as a referee.

“You can teach me to ride in here,” she declared, “with a pretend throttle.”

“We can teach balance,” Dr. Chen corrected. “What do we think about starting on two feet?”

They started with basics: how to stand and breathe when you’re nervous, how to feel the ground with your shoes, how to look where you want to go instead of where you don’t. Caleb had never taught a child those things, not on purpose, but his body knew them. He translated muscle memory into sentences the way you translate a song into a hum.

“Pretend the room is a curve,” he said, walking the masking tape line with her. “We don’t fight it. We lean into the bend. Slow is not scared. Slow is skilled.”

Maya bit her lip in concentration and did exactly what he did. Eleanor filmed three seconds—no faces, no names—because future courage sometimes needs proof it happened once.

When they were done, Maya touched the bead on her zipper. “Can we go outside?” she asked. “Not moving. Just sitting and looking at roads.”

They carried two lawn chairs to the front walk. The street was ordinary—trash bins by the curb, a basketball hoop with a net that had lost two loops, a dog across the way patrolling his fence like it was a job. They sat and watched the light change. A breeze pulled through the ash tree and came away smelling like leaves plus one drop of summer.

“Do you remember when you knew I was there?” Caleb asked without urgency.

“When the jacket smelled like rain on a garage floor,” she said promptly. “And when your hand didn’t panic. Some grown-ups’ hands panic.”

“I’ve had practice holding heavy things,” he said.

They didn’t talk about the canyon. They didn’t talk about the car. They talked about the way sparrows argue like siblings and make up between sentences.

At the end of the hour, Dr. Chen tapped her watch. “Transitions,” she said. “We practice them so they don’t throw us.”

Maya nodded and engaged in the delicate ritual of handing back borrowed time. She pressed the wrench keychain into Caleb’s palm. “You keep this when I keep the jacket,” she said. “Then we both have the same smell.”

“It’s a deal.”

On Friday morning, the River County Chronicle ran a front-page photo of Maya’s bead glinting on the canyon ledge. The headline was soft: Found, Because Someone Looked. Online, the same picture acquired all the internet’s usual armor and teeth. Most comments were grace. A few were knives shaped like questions.

Around noon, Dana called. “Update,” she said. “The medical examiner confirmed Renee’s injuries are consistent with the fall. No sign of anyone else at the scene. I’m telling you because ambiguity breeds rumors.”

“Thank you,” he said. He stared at the far wall of his apartment where a nail held a hat that hadn’t been worn in years. He had the sudden urge to hang the keychain there, let the smell of grease fill up the quiet.

“And,” Dana continued, tone shifting, “I’m fielding media requests. People want quotes that make them feel good. We’re going to decline most. Eleanor agrees. Protect the kid, not the narrative.”

“Good lines,” he said.

“Last thing,” Dana added. “There’s a county emergency planning meeting next week. Someone mentioned you in connection with a citizen idea about ‘slow eyes.’ If you want to talk about it in a structured way, I can get you on the agenda under public comment. No promises, just a lane.”

“A lane sounds right.”

They set it for Thursday evening. He hung up with the rare feeling that a door had opened instead of closing.

The afternoon visit was soft. Maya showed him how she’d taped their routine sheet inside a binder. “So I can carry normal around,” she said. She invited him to smell the cedar scarf—“Smells like your jacket had a baby,” she explained solemnly—and he tried not to laugh loud enough to startle the progress.

When it was time to go, Maya said, “Sundays still count?” Her eyes flicked to Eleanor.

“We can sit and look at roads,” Eleanor said, with the bravery of letting a small thing be big.

Caleb lifted two fingers in the tiny salute she’d invented. “Sundays always count.”

He was halfway to the door when Eleanor touched his sleeve. “You’re careful,” she said, more observation than praise. “I notice the way you wait for yeses.”

“I’ve learned to like them,” he said.

Noong gabing iyon, nagluto siya ng mga itlog sa isang kawali na nakakita ng napakaraming bachelor sa napakaraming taon. Binuksan niya ang radyo at pinatay ulit. Nilinis niya ang wrench keychain gamit ang basahan na parang alaala. Hindi siya tumingin sa balita.

Nag-buzz ang telepono sa 9:17. Inaasahan niya ang isang larawan ng isang star sticker sa isang binder. Ang numero ay kay Dana.

“Caleb,” sabi niya, boses kahit sa paraang nagsasabi sa kanya na sinasadya niya itong i-tune doon. “Ikinalulungkot kong tumawag nang huli. Nakatanggap kami ng hindi kilalang ulat sa pamamagitan ng hotline na nagtatanong sa antas ng iyong pakikilahok. Malamang na wala iyon, ngunit ang pamamaraan ay pamamaraan. Hanggang sa ayusin ko ito, kailangan kong i-pause ang iyong mga personal na pagbisita.”

Nakatayo siya nang napakatahimik, tulad ng ginagawa mo sa isang hagdan sa hangin. “Gaano katagal?”

“Ilang araw,” sabi niya. “Siguro mas kaunti. Mabilis akong kumilos. Alam kong masakit ito. Alam ko rin na lumalaki ang pagtitiwala kapag ipinakita namin ang aming trabaho.”

Tiningnan niya ang keychain sa kanyang palad, naramdaman ang malamig na bigat ng isang maliit, tapat na tool. Sa screen niya, may dumating na text mula kay Eleanor, bago niya masagot si Dana: Maya’s okay. She’s asking if Sundays still count.

Nag-type siya pabalik gamit ang kanyang hinlalaki, ang paraan ng pagtali mo sa dilim. Laging.

Pagkatapos ay itinaas niya muli ang telepono. “Okay,” sabi niya kay Dana. “Magpause tayo. Tawagan mo ako kapag malinaw na ang linya.”

Nang matapos ang tawag, ang apartment ay tumunog nang mas malakas para sa isang beat, na tila ang mga tubo at ang refrigerator at ang lumang orasan sa istante ay sinusubukan ang kanilang mga boses. Inilagay niya ang keychain sa counter at ipinatong ang kamay dito.

Sa labas ng kanyang bintana, sa kalye, isang flyer ng Red Flag Warning ang pumapalpak sa isang poste ng ilaw kung saan pinagtatakpan ito ng isang tao, ang papel ay itinataas at hinahampas nang hindi nag-aalala, tulad ng isang bagay na nagsasanay kung paano maging isang sirena.

News

Nakipagpalit ako ng pwesto sa kakambal kong may pasa at ginawa kong impyerno ang buhay ng asawa niya…

Nakipagpalit ako ng pwesto sa kakambal kong may pasa at ginawa kong impyerno ang buhay ng asawa niya… Ako si…

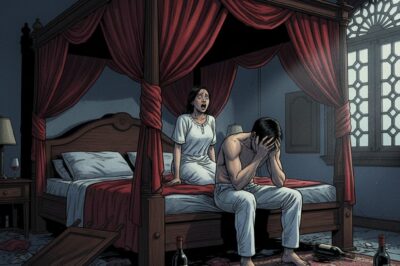

Sa gabi ng aming kasal, gumuho ang aking higaan sa kasukdulan. Akala ng lahat ay biro lang iyon… hanggang sa humagulgol ako nang malaman ko ang tunay na dahilan. At iyon pa lang ang simula ng aking bangungot pagkatapos ng kasal.

Sa gabi ng aming kasal, gumuho ang aking higaan sa kasukdulan. Akala ng lahat ay biro lang iyon… hanggang sa…

Habang inaayos ang air conditioner, natuklasan ng technician ang isang kakaibang bag ng babae na nakatago sa kisame. Pinaghihinalaan ko ang aking asawa ng pagtataksil, hanggang sa binuksan ko ang bag at natuklasang may kaugnayan ito sa sikreto ng aking biyenan maraming taon na ang nakalilipas. Pinaghihinalaan ko rin na may karelasyon ang aking asawa hanggang sa binuksan ko ang bag at nalaman kong may kaugnayan ito sa sikreto ng aking biyenan maraming taon na ang nakalilipas.

Habang inaayos ang air conditioner, natuklasan ng technician ang isang kakaibang bag ng babae na nakatago sa kisame. Pinaghihinalaan ko…

Malayo ang asawa ko dahil sa mahabang biyahe niya sa negosyo, at habang naglilinis ako ng bahay, nakakita ako ng isang pares ng matataas na takong sa loob ng kotse niya. Nang hanapin ko ang may-ari ng sapatos, nagulat ako nang marinig ko ang babae na nagsabing, “Sa… Sa wakas ay natagpuan na rin kita.”

Malayo ang asawa ko dahil sa mahabang biyahe niya sa negosyo, at habang naglilinis ako ng bahay, nakakita ako ng…

“KATARUNGAN SA GITNA NG KAPANGYARIHAN?” Helen Gamboa, Ipinahayag ang Saya sa Kinalabasan ng Pagkilos ng NBI laban kay ‘Tito Sen’—Isang Pangyayaring Yumanig sa Pulitika

🔥“KATARUNGAN SA GITNA NG KAPANGYARIHAN?”Helen Gamboa, Ipinahayag ang Saya sa Kinalabasan ng Pagkilos ng NBI laban kay ‘Tito Sen’—Isang Pangyayaring…

ISANG BLIND ITEM NA YUMAGANAG SA MGA LUBOS NG KAPANGYARIHAN: Paano Isang Tsismis na “Malaswang Panukala” ang Nagdulot ng Isang Senador—at Pamilya ni Raffy Tulfo—Sa Isang Bagyong Pulitikal

ISANG BLIND ITEM NA YUMAGANAG SA MGA LUBOS NG KAPANGYARIHAN: Paano Isang Tsismis na “Malaswang Panukala” ang Nagdulot ng Isang…

End of content

No more pages to load