The day Tatay Ernesto returned home from the hospital in Quezon City, he quietly placed a loan note on the table: about ₱2,000,000. The three of us looked at each other. Kuya Miguel was busy sending his son to college, Kuya Paolo had just opened a shop and was short of capital. As for me – the youngest, everyone called me bunso Rico – I had just gotten married, and I still had a long way to go to pay off my apartment.

But looking at Tatay’s white hair and hunched back, I couldn’t bear it. I took the loan note, signed to pay on his behalf, and then brought Tatay back to live with me so I could take care of him.

A year passed in the small house in the barangay: I worked day and night to pay off the debt, and my meals often consisted of only a plate of boiled vegetables. My wife, Maya, also cut down on all her shopping, even selling her newly purchased scooter. In return, I saw a rare smile on Tatay’s face every time she was with her grandchildren.

Exactly one year after I signed the papers, Tatay called me into his room. He opened a drawer, took out a folded A4 sheet, and placed it neatly in front of me:

Anak, read it.

I opened it… and was stunned. It was not an IOU. Nor a thank you. It was a will: stating that the entire 3-storey house on the main road in Quezon City, along with a 300-square-meter plot of land right in the Poblacion area in the center of a town in Batangas, were all left to me.

I looked up. Before I could say anything, Tatay smiled:

All my life, I just wanted to know… who would be sincere to me in difficult times.

My eyes stung. Just then, footsteps could be heard outside the door. Kuya Miguel and Kuya Paolo stood there, their eyes glued to the will in my hand, their faces changing color slightly.

The conditional will & the secret of the promissory note

The sound of Kuya Miguel and Kuya Paolo’s slippers stopped at the door. Their eyes were fixed on the will in my hand. Tatay Ernesto gently pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose, his voice even and firm:

— I will not share anything today. I only read to you my will, which was notarized by Atty. Alvarez of Timog Avenue, signed by three witnesses: Kapitana Lita, Mang Rodrigo (kagawad) and the neighbor Dr. Cruz. If you want to object, you can do it according to the law. Now, close the door for me.

The door closed, the small room suddenly became dense. Kuya Miguel was the first to speak:

— You are too biased. What does Bunso have that is better than us?

I was about to argue, but Tatay raised his hand to stop me:

— He is not better than us. He just did not leave me in times of trouble.

The sentence fell like a small stone, but the ripples spread far and wide.

In the following days, the Viber family group was ablaze with announcements. Words were flying, and even relatives in the barangay were talking. Before the dust settled, Kuya Paolo sent a short message: “Meet at the barangay hall this afternoon.”

The community mediation session was over quickly. Kapitana Lita just sighed: “Only the court can resolve this matter.” And so, everything was brought to the RTC Quezon City.

Before the opening day, Atty. Alvarez made an appointment with the whole family at the office. He pulled out a thick envelope and placed it on the table:

— Before you guys fight each other in court, there is something Tatay Ernesto wants to announce while he is still lucid. If you don’t listen today, tomorrow it will become an attachment to the file.

Kuya Miguel folded his arms, Kuya Paolo leaned forward. I was silent beside Maya. Tatay slowly:

— The ₱2,000,000 I borrowed… I didn’t give it to you.

The conference room suddenly turned cold. Atty. Alvarez opened the envelope and slid out a stack of papers: transfer, receipt, text message printed from an old phone, and bank confirmation.

— ₱1,100,000 was borrowed in his name to pay tuition & placement fee for Miguel’s children because the foreign school admission fee was too urgent. The remaining ₱900,000 was advanced by Dad to Paolo to rotate in the import of goods after the small warehouse fire in Caloocan. Both times, the children asked “not to tell anyone so that we can save face with our wives and children”.

Miguel’s lips trembled:

— Dad… why didn’t you tell me? I… I thought…

— I thought you had enough money? — Tatay smiled kindly but sadly — Dad only has his back and the PhilHealth. Dad doesn’t want his children to drop out of school, nor does he want you to become debtors to the supplier. Dad signed the loan. Then Dad brought the debt note home and placed it in front of the three of you. Dad is waiting for whoever dares to stay with him.

No one said anything more. There was only the sound of the clock in the room “tick… tick…”.

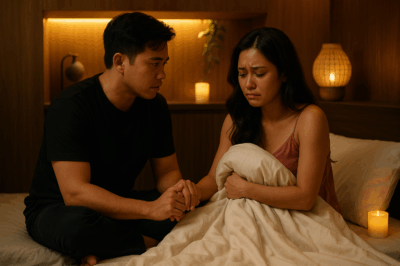

Maya squeezed my hand. I saw Kuya Paolo bow his head, his palms clenched until they turned white.

— So… all this time bunso has been paying for… paying for us? — Paolo hoarsely.

— Yes. — Tatay exhaled — But I’m not telling you to blame you. I just want you to know the truth, before the court asks.

He looked straight at his sons

Dad also did not let the house be a bait for division. The will was conditional: Bunso Rico was to inherit the usufruct (right to use, benefit) for life of the 3-story house in Quezon City. As for the 300m² lot in Poblacion, Batangas, Dad had Atty. Alvarez draw up a contingency subdivision plan: 100m² to Miguel if he personally took care of Dad every Saturday for 1 year; 100m² to Paolo if he paid off ₱900,000 to bunso in 18 months and personally cooked Sunday meals for the family every week; the remaining 100m² and the main house belonged to bunso. If not, whose share would automatically go to the Ernesto Scholarship Fund for needy children in the barangay — signed and notarized trust papers attached.

I was stunned. Miguel opened his mouth, then closed it again. Paolo turned his face, quickly wiping away the tears.

— Attorney, is this condition… acceptable to the court? — Miguel asked softly.

Atty. Alvarez nodded:

— A will with conditions that are not against the law is still valid. The court only considers the cognitive capacity when making the will, the witnessing procedure, and notarization, but does not interfere with the legitimate will of the testator.

The first probate session, RTC Branch 102. The courtroom was filled with coughs. Tatay stood, his hands on the podium, clearly answering each question about the time of making the will, the three witnesses, and the reason he wanted to “change the division method”. Miguel’s lawyer withdrew his objection mid-sentence. Paolo did not argue further — he asked the court for time to “rearrange everything”.

Leaving the courthouse, it was raining in Quezon City. The porch in front of the courthouse had a long leak. Miguel walked behind me, mumbling:

— Bunso, I’m sorry.

I turned to Paolo. He didn’t look at me, just at Tatay, his eyes red:

— I’ll come early this Saturday. I’ll start cooking Sunday dinner.

Tatay laughed loudly, his laughter crisp and shaky:

— So my dream has come true. The first month, Paolo paid ₱50,000. The money was small, but Sunday dinner smelled of sinigang. Miguel stuck to his Saturday routine: taking his son to sweep the yard, installing light bulbs, changing faucet gaskets, taking Tatay to get his heart checked at East Avenue. I still worked at night, but the laughter in the house started to increase.

Then one evening, Tatay coughed violently. Maya panicked and called for a car. I held him on the Philippine Heart Center emergency bench, listening to the monitor’s constant beeping. Miguel and Paolo ran over, their raincoats still dripping.

In the middle of the night, the doctor came out and said softly: “It’s okay, but you have to avoid overexertion. Family members take turns staying on duty.”

That night, the three brothers sat together until dawn for the first time in a long time. No one talked about real estate. They only told stories about their childhood in Poblacion, about how Nanay, who had passed away, liked to eat suman with mango. Tatay slept peacefully, sometimes vaguely moving his lips as if calling our names.

On the 365th day after the court accepted the case, the probate decision took effect. Atty. Alvarez called the whole family to receive a certified copy. He handed me another thin envelope:

— This is Tatay’s “second letter,” with instructions to open it after the court issues the decision.

I opened it with trembling hands. His signature:

“Rico,

If you are reading this, the will has been accepted by the court. But I have one last secret: The money you paid for the past year, Atty. kept in an account called ‘Ernesto Family Trust – for Rico’. I balanced it to pay the monthly interest on the rent for the small kiosk in Poblacion. I did not use the principal you paid. I just wanted to see if, when you thought you had lost everything, you would still choose your family.

That account is yours now. You can decide: keep it, or share it. I am not forcing you.

But if possible, I would like to see all three of you sign the Ernesto Scholarship Fund. Give the kids in the barangay the opportunity you had — or lacked.

— Tatay.”

I was stunned. The sleepless nights, the plates of boiled vegetables, the scooter Maya had sold… it turned out that everything was kept intact. I looked up. Miguel looked at me, Paolo bit his lip, both of them waiting.

— I won’t take it back alone. — I said slowly — I’ll keep half to pay off the mortgage. The other half will be set up as an Ernesto Scholarship Fund this week. The three of us will sign the name on the fund. But you have to fulfill Tatay’s conditions until the deadline. Not for the land, for the promise to my father.

Miguel nodded immediately, Paolo nodded later, but nodded firmly.

— And… — I looked at Atty. Alvarez — the 100m² of land that belongs to you two, I will only accept the transfer documents after 52 Sundays and 18 payments. Everything is public. Not a week less, not a period late.

— A real man. — Tatay stood up, leaning on his cane — That’s what brothers are.

He smiled, but the corners of his eyes were moist. Maya turned away, secretly wiping away her tears.

The following weeks were filled with the smell of rice and soup in the Quezon City house. Paolo learned to make caldereta, Miguel practiced mixing kapeng barako. Tatay had another habit: every meal, he would take a list of poor students in the barangay, and put a blue ballpoint pen next to the names of those who “made good efforts”.

On the day the Ernesto Scholarship Fund distributed the first scholarships at the barangay hall, Kapitana Lita shook the three brothers’ hands, saying as if concluding a long meeting:

— There are debts that can be paid with money. There are debts that can only be paid with love. Today, both are done.

Tatay looked at us, his smile deepening into a groove, his old hand intertwined with his three sons’, and Maya’s hand was superimposed on it. I suddenly thought, perhaps the three-story house, the Poblacion land, and the stack of notarized papers… were all just props. The real play was how each person chose to stand next to each other.

And for the first time since I held the IOU, I felt light as the wind.

— Salamat, Tatay.

— Salamat, mga Kuya.

The words “thank you” came out in both Vietnamese and Tagalog, sounding awkward but warm. Outside, the afternoon sun cast gold on the newly hung sign: “Ernesto Scholarship Fund — Para sa Kabataan ng Barangay.”

End of part 2.

News

Nangako ang aking ina na ibibigay sa akin ang lupa at sinabi sa akin na huwag sabihin sa aking asawa, tumalikod ako at sumagot ng isang pangungusap na ikinadismaya niya./hi

My mother promised to give me a piece of land and told me not to tell my wife, I was…

Afraid that his wife would bring money back to her parents’ house, the husband secretly installed a surveillance camera and was shocked to see the transaction between his wife and her mother-in-law…/hi

Afraid that his wife would bring money to her parents’ house, the husband secretly installed a camera and was shocked…

Happy to have “win over” the most beautiful girl in the school, sa sobrang takot ko tumakbo ako palayo nung makalapit ako sa kanya./hi

Happy to have “struck down” the most beautiful girl in the company, I panicked and ran away when I got…

Tiniis ko ang hirap na mabuntis sa katandaan para magkaroon ng tagapagmana ang aking batang asawa, ngunit sa hindi inaasahang pagkakataon, pagkatapos lamang ng 3 buwan ng pagbubuntis, natuklasan ko na ang aking asawa ay “nang-aakit” sa isang dalaga. Palihim kong binago ang pangalan ng maybahay sa aking telepono, at kinaumagahan ay nakita ko siyang nag-panic…/hi

I endured hardships to get pregnant at an old age so that my young husband could have a successor, but…

Since the day her husband brought his lover home, every night his wife puts on gorgeous makeup and leaves the house. Her husband immediately follows her and is shocked to see this scene…/hi

Since the day Marco brazenly brought his young mistress to live with him in his house in Quezon City with…

Inihatid ng doktor ang sanggol ng dating magkasintahan, namumutla nang makita ang bagong silang na sanggol/hi

The obstetrics ward was packed that day. A frontline public hospital in the heart of Manila was rarely quiet. Dr….

End of content

No more pages to load