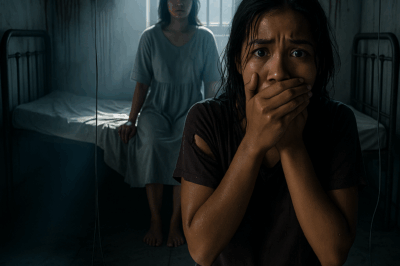

I was tired of coming home and seeing my wife giving birth to only daughters. I tried so hard to have a son, but the more I looked, the more I felt that he was not like me. I left my children to follow my lover for a week. When I returned, my eldest daughter came into the house and said something that scared me…

I was tired of coming home and seeing my wife giving birth to only daughters. I tried so hard to have a son, but the more I looked, the more I felt that he was not like me…

In barangay San Isidro, Quezon City, people whispered:

— “That family must have had a bad karma, not having a son to continue the family line…”

I am the eldest son in the family. My father had four brothers, but the first three of my children were all girls. My wife, Liza, suffered because of the gossip. On the fourth occasion, she gritted her teeth and kept him even though the doctor said he was in poor health. When I found out it was a boy, I cried tears of joy.

But the older he got, the stranger he became. His skin was pale, his eyes were single-lidded, and his forehead was protruding. While I was dark-skinned, with deep-set eyes and a broken face. I began to doubt.

When I was angry, I would taunt my wife:

“Are you sure that it is my child?”

Liza cried her eyes out. My eldest daughter, Ana, 13, just silently looked at me with resentful eyes.

One day, I secretly left home to follow my lover Shaira — a hairdresser at a salon on EDSA, 10 years younger than me. She whined:

“I gave birth to two sons for you, not like that other woman…”

I was blind. I didn’t bother to call home, regardless of whether my wife and children lived or died. For a week, I stayed with Shaira in a rented room in Mandaluyong, dreaming of a family “just like mine”.

Until that afternoon…

it was drizzling in the habagat season — I returned home with the intention of getting a divorce.

As soon as I opened the door, the girls sat there silently, their eyes red. Ana stepped forward, pointed toward the room, and coldly said:

“Come in and see mom for the last time…”

I was stunned.

I rushed in. Liza lay there, pale as a sheet of paper, still clutching the unfinished letter. The baby had been carried to the next house by the kapitbahay (neighbor). She had taken sleeping pills — the kind I had bought for my lover…

I screamed, shook my wife awake, and called for help. But it was too late.

The last letter was only a few lines long:

“I’m sorry. I kept my son because I thought you would love me more. But when you left, I knew I had lost. If there is a next life, I still want to be the mother of your children, even if I can’t be your wife anymore.”

I held my head and sat down on the floor, listening to the children’s cries echoing like knives stabbing my heart. As for Shaira, when she learned that I had a wife who died because of her, she panicked and cut off contact, disappearing that very night.

After the funeral at the Caloocan cemetery, I carried the baby home, stood in the middle of the rain-soaked barangay, and watched my daughters hold hands. I understood that everything I had been searching for all this time — “continue the family line,” “be like me,” “a man must have a son” — had turned out to be just a shadow that had led me astray.

Family is not a genetic test, nor is it a place for the ego to swell and suppress the tears of women and children. If there is anything left in life, it is the father’s hand that never lets go of his child when he cries, and the husband’s shoulder that never turns away when his wife is weak.

But I was too late… And for the rest of my life in Quezon City, every time the habagat rain splashed across the tin roof, I would hear Liza sighing in the small house: “Just stay.

News

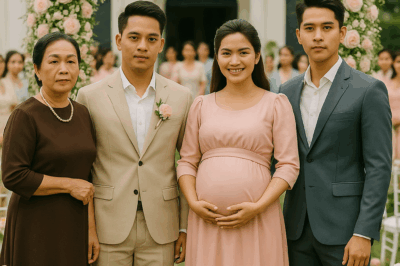

Shaira Diaz and Edgar Allan Guzman WEDDING❤️FULL VIDEO ng KASAL ni Shaira Diaz at EA Guzman/hi

After twelve patient years that felt like a slow sunrise, Shaira Diaz and Edgar Allan “EA” Guzman finally stepped into…

Isang dalagang hindi makalakad ang nakarating sa animal rescue center. Ang ginawa ng pinakamabangis na German Shepherd ay nagpasindak sa lahat…. …/hi

A girl in a wheelchair walked into an animal rescue center in Quezon City, Metro Manila. “I want to see…

Pinakasalan Niya Ako Nang Hindi Ako Hinahawakan — Pagkatapos Nakakita Ako ng Isang Nakatagong Kwarto Sa Ibang Babae…/hi

He Married Me Without Touching Me — Then I Found a Hidden Room With Another Woman… From the outside, our…

Nagpakasal ako sa isang construction worker para gawing legal ang pagbubuntis ko. Noong 3 years old ang anak ko, kinilig ako nang makita ko ito sa wallet ng asawa ko. Hindi ko inaasahan na magiging ganoon siyang tao…/hi

I married a construction worker to legalize my pregnancy. When my child was 3 years old, I trembled when I…

Noong araw na muling nagpakasal ang kapatid ko, inimbitahan ng nanay ko ang kanyang dating hipag na sinasabing “infertile” para sumaksi. Nang siya ay lumitaw, ang aking ina ay hindi tumayo, dahil sa tabi niya ay/hi

The day my brother remarried. My mother invited my ex-sister-in-law who was said to be “infertile” to witness. When she…

SHOCK 😮Trahedya ng Miss Philippines: Inang May Tatlong Anak na Brvt@l n@ Pin@tay — Ang Katotohanan sa Likod ng Kamatayang Niyanig ang Buong Bansa/hi

The tragic life of the Philippine beauty queen who was brvt@lly mvrdered: A single mother of 3 children and a…

End of content

No more pages to load