When I was seven, my father remarried with eyes as sharp as knives, the discrimination between stepchildren and biological children made me unable to bear it and I left home. Twenty years later, I heard the shocking news and returned home to see an unbelievable scene. When I was seven, my father remarried. People said that “stepmothers” were hard to love, and it was true: Tita Liza – Tatay’s second wife – had eyes as sharp as knives, and her words were full of criticism. Meals at the small house in barangay Tandang Sora (Quezon City) were always filled with tears. Her biological children ate hot chicken tinola, wearing new uniforms; I wore a patched shirt, sipping a bowl of thin soup. Unable to bear the discrimination between “biological children and stepchildren”, one night when the rain was pounding on the corrugated iron roof, I quietly carried my worn backpack, followed the dark alley, and swore that I would never return to that house in this life.

Twenty years later, amidst the hustle and bustle of life in a foreign land – I was working as a hired hand in the Middle East like many OFWs – I received the bad news: Tatay Ramon had passed away. Feeling both angry and sad, I quickly flew back to Manila to mourn.

On the day of my return, the whole neighborhood came to the lamay, everyone’s eyes filled with concern. I entered the house, placed an incense stick in front of Tatay’s portrait, then a stooped figure approached. I looked up – and was so stunned that I dropped the bundle of incense sticks in my hand.

The woman from back then – my “dark stepmother” – was now an old lady with gray hair and cloudy eyes. She trembled as she held my hand, her mouth stammering: “Anak… anak ko.” That call made my chest tighten.

The neighbors whispered, like knives piercing my heart

“When Tatay was sick, Aling Liza sold all her alahas (jewelry), working hard to pay for medicine. But after the motorbike accident a few years ago, she became senile… she claimed everyone as her child – biological or illegitimate, all ‘anak’.”

I was speechless. Years of hatred suddenly disappeared like incense smoke. The woman I had cursed, now sat trembling, holding my hand as if afraid of losing it, her mouth only knowing how to call “anak.” I knelt down, placing my forehead on the back of that wrinkled hand. In the corner of the house, the lamay lamp flickered; outside, the sound of a tricycle passed by, the wind carried the scent of jasmine mixed with incense smoke.

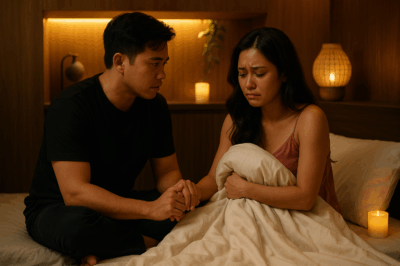

That night, I sat next to her. She was sometimes awake, sometimes unconscious, telling mixed stories: “When you were little… your shirt was torn, your mother sewed it. Don’t go anymore, stay home with Tatay.” I held her hand, whispering: “Yes, I am here.” No more “stepchild – common child,” just the word “anak” that choked me to the point of speechlessness.

The next morning, I went to the palengke market at the end of the alley to buy a pot of hot lugaw for my grandmother. On the wall, a portrait of Tatay Ramon looked down kindly. I suddenly understood: there are wounds that only time and compassion can heal. I turned back, poured her a sip of warm water. She looked at me, smiled gently: “Salamat, anak.”

For the first time in twenty years, I stepped through the threshold of the old house without feeling like an outsider. I had returned – not to demand justice, but to learn to forgive. And her “anak,” amid the incense and novena prayers, was the gentlest answer to my stormy childhood.

News

Nangako ang aking ina na ibibigay sa akin ang lupa at sinabi sa akin na huwag sabihin sa aking asawa, tumalikod ako at sumagot ng isang pangungusap na ikinadismaya niya./hi

My mother promised to give me a piece of land and told me not to tell my wife, I was…

Afraid that his wife would bring money back to her parents’ house, the husband secretly installed a surveillance camera and was shocked to see the transaction between his wife and her mother-in-law…/hi

Afraid that his wife would bring money to her parents’ house, the husband secretly installed a camera and was shocked…

Happy to have “win over” the most beautiful girl in the school, sa sobrang takot ko tumakbo ako palayo nung makalapit ako sa kanya./hi

Happy to have “struck down” the most beautiful girl in the company, I panicked and ran away when I got…

Tiniis ko ang hirap na mabuntis sa katandaan para magkaroon ng tagapagmana ang aking batang asawa, ngunit sa hindi inaasahang pagkakataon, pagkatapos lamang ng 3 buwan ng pagbubuntis, natuklasan ko na ang aking asawa ay “nang-aakit” sa isang dalaga. Palihim kong binago ang pangalan ng maybahay sa aking telepono, at kinaumagahan ay nakita ko siyang nag-panic…/hi

I endured hardships to get pregnant at an old age so that my young husband could have a successor, but…

Since the day her husband brought his lover home, every night his wife puts on gorgeous makeup and leaves the house. Her husband immediately follows her and is shocked to see this scene…/hi

Since the day Marco brazenly brought his young mistress to live with him in his house in Quezon City with…

Inihatid ng doktor ang sanggol ng dating magkasintahan, namumutla nang makita ang bagong silang na sanggol/hi

The obstetrics ward was packed that day. A frontline public hospital in the heart of Manila was rarely quiet. Dr….

End of content

No more pages to load