Because I Couldn’t Give Birth to a Son, I Was Kicked Out of the House by My Mother-in-Law Just One Day After Giving Birth. What Happened After That Left Everyone Stunned…

Early in the morning, the heat from the rising sun filtered through the window and cast its light onto the antique tiled floor of the two-story house nestled deep in a narrow alley in the outskirts of Hanoi. The kitchen echoed with the clinking of dishes and the fragrant smell of sour fish soup, filling the air with a gentle, comforting aroma, much like the warmth of a woman quietly working by the stove.

Hường, a 32-year-old woman with a petite frame, a sharp nose, and delicate skin, but hands roughened by years of household chores, was carefully seasoning the soup for the last time. At the small wooden dining table by the window, her eight-year-old daughter Linh was teaching her younger sister Lan how to fold paper into cranes. As they worked, Linh animatedly chatted about school, her large, bright eyes sparkling with energy.

Lan, as usual, giggled, playfully tugging at her sister’s hair, babbling on about how their teacher had sung the wrong lyrics to a song. Hường smiled, a soft, gentle smile that wasn’t bright but quietly warm like the morning breeze. She turned back to the table and poured another glass of milk for the two girls, a feeling swelling inside her that she couldn’t quite name.

It could be called happiness, but it was a fragile kind of happiness, one that slipped away just as soon as she thought she had a firm grip on it. To outsiders, everyone would say that Hường’s life was the dream of many women. A husband with a good job, a big house, two smart and well-mannered daughters. But only Hường knew that there was always something that made her feel like she was living in someone else’s house.

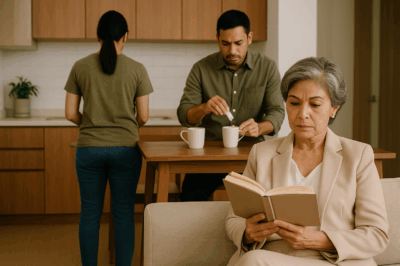

The shadow of her mother-in-law, Miss Thảo. Miss Thảo wasn’t fierce, she didn’t raise her voice, nor did she scold openly. But every word she spoke was like a cold, biting layer of frost, cold enough to make one afraid to even breathe too loudly. The woman, in her sixties, had a slender frame, a calm and gentle face, and always wore a dark silk blouse with a high collar, exuding a dignified composure.

But in her deep, dark eyes, Hường could clearly see that she had never truly been accepted. And the reason was clear without asking: Hường had given birth to two daughters. Since the birth of Lan, bà Thảo’s gaze had changed. Not with reproach, not with tension, but every now and then, bà Thảo would sigh during meals or quietly flip through the family genealogy book in the living room before closing it with a click—a silent warning.

Her passing remarks like “Girls grow up and leave their families. Who will offer incense for our ancestors in the future?” At first, Hường thought it was just idle chatter, but she soon realized they were deliberate words, like poison dripping slowly into her mind. That morning, as Hường was cleaning the dishes, she heard the soft shuffle of bà Thảo’s slippers on the stairs. Bà Thảo was coming down, holding a cup of hot tea, her eyes fixed on the dining table.

“Linh, Lan, still folding paper cranes? Don’t let any scraps fall on the floor,” she said lightly, before turning to Hường and continuing the conversation as if casually chatting. “Hường, yesterday, our neighbor Mrs. Hiền came over to show off her grandson. He’s two years old now, a lively, cute little thing, and both grandparents carry him around the village to show off.” Hường paused, her hand slowing down as she wiped the dishes, trying to maintain her composure.

“Yes, it’s great that he’s healthy, mother,” she replied. bà Thảo smiled and took a sip of her tea. The conversation ended right there, as it always did, but Hường understood that it was another disguised criticism sent her way.

Khang, Hường’s husband, was a quiet, calm, and gentle man. He was the head of the technical department at the family’s mining company, where bà Thảo had been a major shareholder before retiring. To many, Khang was the perfect husband: he worked hard, came home on time, loved his wife, and cared for his children. But to Hường, sometimes his gentleness hurt her more than harsh words ever could.

Every Time bà Thảo Hints About Having a Grandson, Khang Just Silently Holds My Hand and Says, “I Don’t Care About the Son or Daughter, Don’t Think Too Much.” But I Know, the More He Says This, the More Lonely I Feel…

Because the burden doesn’t lie in what my husband says, but in the gaze of my mother-in-law, who shares the same house.

Every night, as we lie together, Khang gently strokes my hair and says, “If you want to have another child, go ahead. Don’t do it because of your mother, but for us.” I stay silent. I can’t tell him that every time I look into bà Thảo’s eyes, I feel like I’m living in someone else’s house, that I’ve given birth to children that weren’t what she had hoped for, and I’m being judged like an animal that hasn’t reached standard.

Days pass by, seeming peaceful on the surface, but they carry with them something that silently festers beneath.

Every morning, it’s the same routine: I wake up early to cook, take the children to school, and water the plants in the garden—the rose garden that bà Thảo loves so much. But I feel as though every step I take is being watched, and every small gesture could be judged.

One weekend afternoon, while I was hanging the laundry, bà Thảo came over, holding a small red bag. She gently placed it on the stone table in the yard, speaking in her usual calm tone.

“Hương, a few days ago I went to Trấn Vũ Pagoda and met a very famous nun. She gave me this amulet and said if I hang it above the bed, the couple will be able to have a son. I think you should try it; just leave it there, who knows?”

I looked at the amulet in silence, not because of the object itself, but because of the underlying message: “Have a son before it’s too late.” I tried to keep my voice calm. “Thank you, Mother, but I believe children are a gift from heaven. We should just let things happen naturally.”

The words barely left my mouth when bà Thảo paused, her smile fading. Her dark eyes became distant, and she nodded slowly.

“Fine, if that’s what you think. But I believe people still need to make efforts to bring good fortune. You can’t just wait forever.”

That night, as I lay alone in the room, I listened to the soft sound of rain falling on the window. I stared up at the ceiling, my hand on my stomach, where a tiny life was growing, though even I wasn’t sure yet.

A few days earlier, feeling nauseous and exhausted, I quietly tested for pregnancy. Two clear lines appeared on the test. I didn’t tell anyone—not even Khang. Not because I wanted to hide it, but because I was afraid. Afraid that if it was another girl, bà Thảo wouldn’t just stop at words this time.

I didn’t know yet that this pregnancy would be the turning point that would push me out of what I thought was my home, into a storm of turmoil, and eventually lead me to the awakening I would need. I didn’t tell anyone about the pregnancy.

I didn’t know if I should feel happy or sad; all I felt was a heaviness. I hid the pregnancy test in a drawer in the wardrobe, along with things that couldn’t be named: old ultrasound papers, a half-finished journal, letters from my deceased parents that I had kept since marrying Khang.

Khang continued his routine, going to work, coming home for dinner, and playing with the children. But he seemed tired—not from work, but from standing between two women.

One woman he was born to, and the other he chose to spend his life with, but he never truly picked either side. I knew Khang loved me, but I also knew that love wasn’t strong enough for him to protect me from his mother, at least not in the most crucial moments.

I planned to wait until the 12th week before seeing a doctor. I didn’t want bà Thảo to find out too soon. I didn’t want the looks, the silent questions. But sooner or later, it was bound to happen.

One weekend morning, while I was watering the hibiscus flowers outside, bà Thảo came back, holding a red paper bag tied with golden thread.

She called me into the living room, her voice calm as always. “Hương, I just came back from a visit to the temple. I met a famous nun, and she said it’s very accurate. I mentioned our family situation, and she predicted that if you don’t hurry, the family line will be cut off. This time, you must give birth to a son.”

I looked at the bag. I didn’t even need to open it to guess what was inside. It could be an amulet, medicine, or perhaps a curse wrapped in blind faith.

I sat down, keeping my voice calm. “Mother, I believe children are given by heaven. I’ve been blessed with two well-behaved daughters. I think that’s already a blessing.”

“Blessing?” bà Thảo raised her eyebrows. “You call that a blessing? Don’t you think about your husband? He’s the only son. Who will carry on the family name?”

I bit my lip. I wanted to say that whether a child is a son or a daughter doesn’t define their character or the love in a family, but I knew those words would mean nothing to someone who didn’t want to hear them. I simply said softly, “I understand your expectations, Mother, but I ask that you don’t pressure me into doing something I don’t believe in.”

Bà Thảo was silent for a moment, then placed the paper package on the table. Her voice was cold. “I’m not pressuring you. I’m just warning you that if you have another daughter this time, I won’t tolerate it anymore.”

Hường stepped out of the room, as though a cold wind had just struck her back. She went to her room, opened the wardrobe, and took out a thick coat, pressing it firmly against her stomach as if to protect the small life that was beginning to form inside her. That night, Hường sat beside Khang after the two children had fallen asleep.

She decided to speak, “It’s not to ask for permission, but to let you know, because if I don’t share this, I’ll feel more alone than ever.”

“Khang, I’m pregnant.”

Khang looked at her, stunned for a moment, then smiled and hugged her tightly. “Really? Oh my god, thank you!” He kissed her forehead, as though the joy of becoming a father for the first time had just flooded over him.

“Are you tired? Do you feel nauseous? I’ll take you to the doctor tomorrow,” he said warmly, his hand gently stroking her hair.

In that moment, Hường felt loved. But just seconds later, he asked, “Do you think this time it will be a boy?” The question wasn’t malicious, but it pierced through the fragile happiness she had just inflated like a balloon. She simply nodded, suppressing a sigh.

She knew that although he said it didn’t matter, deep down, he too was hoping for the same thing everyone else was—a child who could redeem her position in this house.

Six weeks later, Hường went to the doctor alone. Khang was busy with a meeting, and bà Thảo still didn’t know. On the ultrasound screen was a tiny spot moving, with a heartbeat.

She didn’t ask the doctor about the baby’s gender. She didn’t want to know. Not because she didn’t care, but because she knew that if it was a girl, her joy wouldn’t be shared. It might even be rejected. She placed her hand on her stomach as she sat on the bus home. The baby, unaware of the noise and chaos around it, had no idea that its existence was the cause of a silent war between a mother protecting her child and a grandmother fiercely guarding her family’s lineage.

A week later, Khang received an urgent business trip abroad. There was a technical issue with the project in Indonesia, and he had to fly out early, staying at least a week. Before leaving, he told her, “I’ve already told my mom. Just rest and don’t worry. She’ll take care of everything.”

Hường forced a smile. She didn’t say that she couldn’t rely on his mother, but she didn’t want to make him uncomfortable.

Deep down, she knew the silent battle would begin the moment the door closed behind him. Less than two days after Khang left, bà Thảo began to change. No more subtle hints, no more mornings with fake inquiries about her well-being. She switched to open confrontation.

That afternoon, bà Thảo called Hường into her room and handed her a small bottle of brown liquid with a pungent smell.

“This is a pregnancy tonic, from the lady at Mễ Trì Temple. Drink it,” bà Thảo said, her tone firm.

Hường stared at the bottle, feeling a knot of suspicion in her chest, but she couldn’t refuse. bà Thảo stared at her intensely, like a police officer questioning a suspect.

“Are you going to ask a doctor first?” bà Thảo asked.

“The doctors? Those Western-trained ones? What do they know compared to traditional experience? Cô Mùi has helped with hundreds of cases!” bà Thảo’s voice was rising in frustration.

Hường didn’t dare argue, but she didn’t want to drink it either. That night, she hid the bottle in the drawer of her private room, under the old, faded wedding dresses.

The first summer rain fell that night. The sound of raindrops on the metal roof mixed with Hường’s rapid breathing in the darkness. She couldn’t sleep, her hand still resting on her stomach, where the baby was lying.

She whispered softly, her voice breaking, “My dear, whether you’re a boy or a girl, I will love you. I won’t let anyone hurt you. I promise.” But inside her, a storm was brewing. She knew that from the moment Khang boarded the plane, bà Thảo was quietly preparing a cruel decision—one that Hường didn’t expect, but couldn’t avoid.

The next morning, Hường woke up with a dull pain in her lower abdomen. She sat up slowly, washing her face while trying to ignore the slight cramps that were starting to come and go. She didn’t dare groan or show any sign of pain. bà Thảo was still sitting in the living room, watching the news, the TV’s cold voice filling the room like the chill of the season.

When Hường went out to prepare milk for the children, bà Thảo glanced at her stomach, which had visibly grown. It was no longer something she could hide, but bà Thảo didn’t say a word. Her gaze was as cold as if she were looking at something foreign—something that didn’t belong in this house.

The entire morning, bà Thảo didn’t ask a single question. Not about food, not about her health, not even about her pain. Hường moved around quietly, both because of the pain and the fear. She knew that bà Thảo’s silence wasn’t kindness, but the silence of a judgment yet to be pronounced.

Around 10 a.m., the pain became intense. Hường gritted her teeth and grabbed her phone to call a taxi.

She called the children over to kiss their foreheads, telling them to stay at home and behave. “Mom will be back soon. If anything happens, just tell grandma.”

Linh clung to her sleeve, her voice trembling, “Mom, are you in pain? Where are you going?”

Hường smiled, her tears welling up. “It’s okay, sweetie. Mommy is going to pick up the baby.”

The taxi arrived in front of the house, and Hường carried her bag and climbed into the car by herself. No one said goodbye. bà Thảo just stood behind the curtain, glancing at her before sitting back on the sofa as if nothing had happened. She poured herself a cup of tea and sipped it slowly.

Her third labor began that way—lonely, cold, and without any familial support. Two days later, Hường gave birth.

The baby was a tiny girl, red and wrinkled, crying weakly but with bright eyes. The doctor placed the baby on Hường’s chest, and she held her as though she were holding the very reason to keep living. No one came to visit. No bouquets, no sounds outside the door. Hường took a photo of her newborn daughter and sent it to Khang and bà Thảo. Khang replied a few minutes later, saying he would be home later than expected.

“But you did great. Please rest, okay? I love you and our daughter.”

bà Thảo didn’t reply. No acknowledgment that the message had been seen. That night, Hường didn’t dare cry. She knew she couldn’t be weak. The baby was lying next to her, needing her, needing a mother who wouldn’t give up.

She named her daughter Minh An, meaning “light and peace.” But inside, everything was growing darker. Two days later, she was discharged from the hospital.

She carried her own bags, carried the baby down to the lobby, and hailed a taxi to go home. And when the gate opened, she understood that she was no longer considered a daughter-in-law. Her belongings—an old suitcase, the baby stroller, and the clothes baskets for the two children Linh and Lan—were neatly arranged right in front of the porch. It was as though someone had already prepared everything for a move, without a single word of farewell.

Bà Thảo was standing at the door, arms crossed over her chest. She looked at Minh An, then at Hường, as if both of them were strangers. “What are you doing here?” Her voice was as cold as metal.

“Mom, I’ve been discharged from the hospital. This is my daughter,” Hường stammered, her shirt soaked with sweat, hands trembling as she held the tiny, still red baby.

“She’s a girl. Do you still have the face to come back here?” bà Thảo spat out each word.

“I didn’t do anything wrong, Mom. I only gave birth to a child,” Hường replied, trying to hold her composure.

“Right, another girl. Do you really think this house is blessed enough to have three daughters? You no longer belong here,” bà Thảo snapped.

Hường was stunned. She hadn’t imagined bà Thảo could be so cruel. To chase away a woman who had just given birth, with blood still staining her clothes, holding a baby who didn’t even know how to nurse properly yet.

“Mom, I just gave birth, I have nowhere else to go.”

“Not my problem,” bà Thảo cut her off. “I’ve already packed your stuff. Take it and leave. I don’t want the children to see your weak, fake face.”

A bag fell to the ground, clattering against the metal gate. The sound of cold metal echoed. Hường bit her lip, holding the baby tightly as she walked away. The pain in her stomach still hadn’t gone away, and her back ached terribly.

But she didn’t cry—not a single tear. Only Linh and Lan, the two children, were standing by the window on the second floor, their faces pressed against the glass, calling, “Mom!”

bà Thảo quickly shut the curtain, blocking out the light, and closed the door. And so, Hường officially no longer had a home. The rain drizzled down as Hường stood frozen by the gate.

She didn’t cry. Minh An had fallen asleep from hunger. Her shoulders were soaked, and her hands carried the bags, while Linh and Lan clung to her dress, their eyes wide with confusion, not understanding what was happening.

Hường had no one to call. Her parents were gone. Her maternal relatives were few and had never truly welcomed her since she married into this family. Her friends were all too busy, and Hường had never complained to anyone.

Her phone was almost out of battery. She couldn’t go anywhere and couldn’t just stand there forever. Without thinking, she remembered the old house—the small house by the river where she and Khang had rented in the first year after they got married. When they had nothing, when bà Thảo still coldly refused to let her live with them, when it was just Hường, Khang, and the sound of rain on the rusty roof.

She called a taxi, not knowing where to go, only knowing she couldn’t stay there. The only place she could remember now was the one place that had once had a roof, even if only in memory. The taxi stopped in front of the old house. Five years had passed. The door was tightly shut, dust covered the steps, and the vines had grown over everything, seemingly swallowing up time.

As she walked up, ready to rest her back against the old doorframe, a man’s voice came from the neighboring porch.

“Is that you, Hường? Oh my god, is that really you?” Hường was startled. A thin but agile man approached. He was wearing an old baseball cap and holding a pair of gardening gloves. His eyes lit up when he recognized her—it was Mr. Hào, the old neighbor who had once lent Khang a ladder and fixed their plumbing without charging them a dime.

“Goodness, what happened to you? You’re soaked through! And these three children…?” Hường didn’t know how to respond. She just forced a smile, then collapsed.

When Hường woke up, it was already dark. The smell of ginger soup and warm clothes filled the air. Minh An was lying in a small bamboo crib, wrapped in a soft blanket, sleeping soundly. Linh and Lan were sitting at a wooden table eating porridge, unusually quiet and well-behaved.

Mr. Hào was busy making a fire, muttering to himself, “Good thing I still had the keys to this old house. The new owners haven’t moved in yet. It would be such a waste to leave it empty, so I clean it every month to keep the dust down. Who would have thought I’d end up needing it today?”

Hường sat up, tears falling onto her pillow. “I don’t know how to thank you enough, Uncle.”

Mr. Hào turned around and waved his hand dismissively. “Thank me for what? When you’re in need, you help each other. Stay here, it’ll be good for all of us. A house feels like a home when it’s filled with people.”

Hường looked around. Everything was simple, but it felt good—there were no shouts, no judgmental looks, no talk of grandsons or family legacies, only the sound of children eating their porridge, the ticking of the clock, and a warmth that she thought she would never feel again.

That night, for the first time in many years, Hường slept soundly.

Minh An’s cheek rested against her chest, breathing steadily as if she had never been rejected by anyone. Outside, the rain fell again, but inside, there was light.

That afternoon, the sky was dark and gloomy. The old house where Hường and her children were staying seemed to sink into silence, nestled quietly in the damp garden after the rain. Mr. Hào had gone to the market, and Minh An was asleep in her mother’s arms, while Linh and Lan were drawing on a piece of newspaper spread across the old tiled floor.

The sound of crayon on paper, the steady breathing of the children—it all made Hường feel peaceful. A fragile peace, one that could shatter with a single knock on the door. And then, there it was—a familiar, urgent three knocks.

Hường opened the door. Standing before her was bà Thảo, wearing a purple ao dai, dark red lipstick, and carrying a shiny handbag. Her posture was as proud as ever, as though nothing had ever happened.

Hường stood frozen for a moment—not because she was scared, but because she was surprised. She hadn’t expected bà Thảo to come. Not the same person who had once turned her back on her outside the hospital, not the same person who had thrown her clothes out onto the porch just because the baby in her womb wasn’t the right gender.

bà Thảo walked in without waiting for the door to be opened, her eyes scanning the old house, gliding over every item as if she were sifting through trash. She stopped in front of the cradle where Minh An was sleeping, frowning.

“Still a girl, huh?”

Hường tightened her grip on Minh An. “Yes, it’s a girl.”

“You’re really cursed, huh? From your past life,” bà Thảo sneered, her voice no longer pretending to be polite. “My grandmother used to say, any woman who gives birth to three daughters in a row is cursed—she only brings disaster to her husband’s house.”

Hường didn’t reply. She knew that the more she argued, the more bà Thảo would push back. bà Thảo sat down on a chair, crossed her legs, and took an envelope out of her bag. She placed it on the wooden table between them, as if laying down a card in a game. “I didn’t come here to beg you. I came to make it clear—don’t ever bring these three children back to that house again. I don’t mind Khang visiting, but don’t turn that house into a nursery for girls.”

Those words were like a slap to Hường’s face—not just because of their blatant insult, but because bà Thảo still couldn’t see her grandchildren as family. To bà Thảo, they were merely shadows of disappointment.

Hường gently laid Minh An down on the mat, covered her with a cloth, and then turned to sit opposite bà Thảo. “Is that all you came here to say?” she asked. “Is that all?”

There was more.

bà Thảo pushed the envelope toward Hường. “This is 20 million. I’m not lacking in mercy, so I’ll help you a little. You raise the children and find yourself a new husband. Khang is still young, his future is long, and he shouldn’t be stuck with these girls for the rest of his life.”

Hường stared at the envelope as if it were a stone that had just fallen from the sky. She wasn’t angry, didn’t shed a tear. She quietly pulled the envelope toward her, opened it, and carefully took out each bill, neatly stacking them before handing them back.

“Thank you, but I don’t need your money.”

bà Thảo was stunned, as if she couldn’t believe the woman who had once trembled before her was now speaking such words. But Hường continued, her voice still calm, “I won’t go back to that house, and I won’t let the children go back either. But it’s not because I’m afraid of you. It’s because I want my children to grow up in a place where there’s real love.”

“You think you’re noble?” bà Thảo sneered. “You have no right to teach me how to be a mother.”

“You’re right,” Hường nodded, “I don’t have the right to teach you how to be a mother, but I have the right to protect my children.”

bà Thảo seemed to be struck by something, her eyes flashing with anger, but her lips remained silent. Before her, Hường was no longer the weak, submissive daughter-in-law. She was quiet but strong, composed like a rock.

“Go home,” Hường said calmly, standing up and walking toward the door. She thought that bà Thảo had said everything she needed to say. But bà Thảo still sat there, unmoving. Perhaps no one had ever dared to speak to her this way before.

bà Thảo glanced around, her eyes landing on Minh An’s small shoes and then scanning the old sweater hanging on the wall—an impoverished yet cozy space. Something in bà Thảo’s gaze shifted for just a moment, but only for a moment.

Finally, she stood up, grabbed her bag, and walked out without looking back. At the gate, she paused for a second. Amid the sound of the wind rustling through the trees, she heard the voice of her daughter calling from inside: “Mom, the baby’s arms smell like milk biscuits.”

Then she heard Hường’s soft laugh. bà Thảo tightened her grip on her bag and walked away.

The taxi stopped in front of the alley as dusk approached, golden sunlight casting long shadows on the dirt road, tracing the silhouette of someone walking briskly. Khang dragged his suitcase, scanning his surroundings as if he wanted to make sure he wasn’t lost in an unfamiliar place. But in reality, this was the first time he had ever been here.

Without his mother by his side, without the familiar shadow of authority to overshadow everything, he entered through the rusty metal gate. He saw the small, shaded yard, several pots of mint and herbs neatly arranged by the porch. Inside, he could hear the sound of two children laughing—Linh and Lan—and the faint hum of someone else.

The humming, Khang had heard it before, somewhere distant, but now it was so close that it made his heart ache.

He stood there for a few seconds, unnoticed. The door wasn’t locked, but he didn’t knock. He wanted to listen a little longer, to watch a little longer. He saw a thin woman, her hair neatly tied up, holding the youngest in her arms while stirring a pot of porridge on the stove. Linh was sitting next to her, peeling peanuts, while Lan smiled broadly at a worn cloth doll.

It wasn’t the scene of a wealthy family, but it made Khang’s heart tighten with a pain that felt like he had missed something precious.

Hường turned around. Her eyes met his—not surprised, not happy, not angry—just silent, as if he were a stranger entering her private space, and she was waiting for him to explain himself.

“Are you okay?” Khang spoke first, his voice hoarse.

Hường nodded slightly. “I’m fine.”

She placed Minh An in the bamboo cradle, then turned to wipe her hands. She didn’t ask about his trip, didn’t mention the day he had been gone, but she didn’t push him away either.

“I just found out my mom came here,” Khang said, his eyes not meeting hers. “I know I’m late.”

“It’s okay,” Hường replied softly. “Mom came to say what she needed to say. I’ve heard it.”

That “it’s okay” hurt more than any accusation. It was like a dull knife that didn’t cut, but it left a gash inside him. He hadn’t protected her.

Khang bowed his head, whispering, “I’m sorry.”

“You don’t need to apologize,” Hường replied. She lifted her gaze, meeting his eyes for the first time. “What I need is a clear choice and the courage from the man I call my husband.”

Khang was silent for a long time.

The wind blew through the crack in the door, carrying the scent of smoke from the stove and the distant crowing of a rooster. Finally, he moved his suitcase closer and placed it by the porch.

His voice trembled, but it was firm. “I don’t want you to live alone anymore. I don’t want our children to grow up without a father. I’m asking permission to stay, if you’ll allow me.”

Hường looked at him. Her eyes were no longer sparkling like they had been on their wedding day, but in them was something that made Khang uneasy.

The calmness of someone who has been hurt enough to no longer expect anything.

“I can stay here,” Khang said quietly, his voice heavy with meaning. “For the children.”

But don’t expect that just a few days, or a few meals, will make everything as if it never happened.

“I don’t expect that,” Khang bowed his head. “I just want to start over, even if it takes a long time.”

Minh An whimpered, then started crying.

Hường turned away, gently lifting the baby and soothing her. She didn’t say anything more, but in that moment, Khang knew that at least the door hadn’t been slammed shut on him. It was the first time he truly realized that he had to learn how to be a father and a husband all over again.

The small house now had one more man, but that didn’t make it feel any less empty.

Khang woke up early, made the bed, swept the yard, and bought vegetables from the market. He fumbled with holding the baby, learning how to change diapers, how to lull the child to sleep. Linh and Lan, who had initially kept their distance, began to come closer. The sounds of “ba” (dad) started to return, a stuttering, hesitant version, like small buds daring to rise after a storm.

Hường remained the same as before—quiet, careful, self-sufficient.

There were more bowls and chopsticks at the dinner table, but the laughter between husband and wife was gone. She still cooked, still cleaned, but didn’t ask him what he wanted to eat. He came home on time, and she didn’t ask how his day had been. She still let him help with carrying the baby, picking them up from school, or mopping the floor, but she wouldn’t allow him to get any closer to her heart.

At times, Khang wanted to start a conversation, to talk about the first days of being a father, to share the nights spent awake with Linh when she cried with colic. But Hường only remained silent—not rejecting him, but not accepting him either. The invisible wall between them was no longer built by anger but by the sediment of old wounds.

On the other side of the city, the once bustling three-story house now stood cold and quiet.

bà Thảo lived alone, her maid had taken leave to return to the countryside to care for her child, and bà Thảo didn’t bother to hire another. Her meals were solitary, with four bowls and plates set on the table, as a habit, but then quietly put away. She still went to the temple, but she no longer bragged about her clever granddaughters or Khang’s talents. She no longer spoke of her precious first grandchild.

It wasn’t because she had changed her beliefs, but because she began to feel that she was being left behind.

One rainy afternoon, bà Thảo opened the wardrobe and found Hường’s maternity dress, which had been forgotten after being washed and hung to dry. The white dress, with a round collar, had stains of cooking oil on it. She picked it up with trembling hands. The scent of soap had faded, but the smell of the person still lingered.

The smell of a woman who had quietly endured, quietly carried a child, quietly given birth, and quietly left, without a word of complaint.

For the first time in many years, bà Thảo felt that she was wrong. Wrong for forcing someone else to live by her beliefs. Wrong for using flesh and blood to bargain. And wrong for thinking that just because she was a mother-in-law, she had more authority than a daughter-in-law.

Sunday afternoon, Khang was fixing the roof over the porch. Minh An was in the cradle, kicking her little legs, while Linh and Lan sat beside her, coloring. Hường brought a tray of water to the small stone table. Khang reached out to take the cup of tea, intending to thank her, but then he noticed Hường pause. Her gaze turned toward the end of the alley, where a familiar figure stood, neither coming in nor leaving.

It was bà Thảo, her hair messy, her dress no longer neat as usual, holding a small plastic bag with a few pieces of bánh đúc (rice cake) and some bananas inside.

No one spoke at first.

Linh saw her and shouted, “Grandma’s here!”

Her words echoed in the quiet space, and Hường furrowed her brows slightly, while Khang stood frozen.

bà Thảo walked slowly toward them, her posture no longer proud, her eyes no longer sharp. She looked at her son, at her three grandchildren, then stopped in front of Hường. One second, two seconds, then she softly asked, “May I hold the baby?”

Hường glanced at Khang, then down at Minh An. She bent down, gently picking the baby up and holding her in her arms. “Please, sit down,” she said calmly. “I’ll make tea.”

There was no gesture of forgiveness, no warm welcoming gaze, but neither was there a door slammed shut. It was just a stone bench under the shade of a tree, a warm cup of tea placed down, and the silence sufficient to begin anew, if one is sincere enough to be patient. Since Mrs. Thao’s visit, no one mentioned it again. Khang didn’t ask his mother, because he knew that for the first time in her life, she came not to control, but to knock on the door of her own loneliness.

Hương didn’t say anything either, but that night, she stood at the window for a long time, looking out at the alley where Mrs. Thao had stood in the fading afternoon light. Three days later, someone knocked on the door. It wasn’t Mrs. Thao, but a delivery person with a cardboard box containing a box of prenatal milk, some baby diapers, and a package of mung bean cakes that Lan liked. There was no name on the box, only three slanted words written in pen: “For Minh An.”

Hương didn’t say anything. She simply brought it inside and put it away neatly. In the days that followed, every weekend, something appeared in front of the door: a bundle of fresh vegetables still covered in dirt, a jar of homemade pickles, a children’s songbook, a new pair of plastic sandals for Linh to wear to school. No one asked, no one accepted, but everyone understood. Mrs. Thao hadn’t said sorry, but she was speaking in the only way she knew: through action.

One afternoon, the sky turned cloudy, and Minh An developed a fever. The little girl cried in Hương’s arms, her breath fast and her cheeks red. Hương, flustered, rushed to the local clinic without having time to remind Linh and Lan. At that moment, someone called from the end of the alley—it was Mrs. Thao. She had brought eggs and some wild greens.

When she saw Hương holding Minh An, trembling, she didn’t say much, just one sentence: “Take the child to the clinic, I’ll stay here to watch the two older ones.” Hương looked at her, and for the first time, she saw not the scrutiny or control she had grown accustomed to, but genuine concern. She nodded. For the first time in many years as a daughter-in-law, she left the house with Mrs. Thao in charge, without locking the door, without suspicion, without any instructions.

When Hương returned, it was already dark. Minh An had been given fluids and was sleeping in her father’s arms. She stepped into the house to find the dining table still set, the rice cooked, and the porridge kept warm. Linh and Lan were sleeping soundly by their grandmother’s side, while Mrs. Thao sat with her back to the chair, eyes closed, her hands still gently holding the hands of her two grandchildren.

Hương didn’t wake anyone up. She sat down, took a warm cloth, and wiped her daughter’s face, then gently covered her mother-in-law with a blanket. Mrs. Thao didn’t open her eyes, but her shoulders slightly trembled, as if she was holding back tears. The next morning, the sky was clear again. Khang left early for work, and the three children were still sleeping. Hương woke up, opened the gate, and saw Mrs. Thao standing at the entrance, fiddling with something in her hands—wrapped sticky rice cakes and a few old comic books.

“Why are you here so early?” Hương asked.

Mrs. Thao looked a little embarrassed. “I was worried that the little one might have a fever again.”

Hương nodded, opened the gate wider. “Come in and have breakfast with the kids. I’ve made some chicken porridge.” There was no smile, no sweet voice, but that was the first invitation Hương had ever given Mrs. Thao after all those years of being a daughter-in-law.

That day, the whole family sat and ate together under the porch. Minh An slept soundly in her cradle, while Linh and Lan fought over who would tell the next story. Mrs. Thao listened quietly, serving porridge to her grandchildren, picking vegetables for her daughter-in-law, and pouring tea for herself. No one spoke about the past, no one demanded an apology, but in the exchanged glances, there was an entire ocean of calm.

At the end of the day, as Hương saw Mrs. Thao out to the gate, she simply said, “Next time, just come in. No need to knock.” Mrs. Thao stood still, then turned back to look at her. “Thank you for still letting me be their grandmother.”

Hương didn’t answer. She turned away, but her eyes were wet. Not all wounds can be healed by a hug, but when someone dares to admit their mistakes and take a step back, love, even if late, can still return.

And sometimes, forgiveness is not in words but in the calmness to cook a warm bowl of porridge, open the gate, and leave a seat at the dinner table.

News

My Husband Put Something in My Coffee. I Secretly Switched It to My Mother-in-Law’s Cup. 20 Minutes Later…/th

My Husband Put Something in My Coffee. I Secretly Switched It to My Mother-in-Law’s Cup. 20 Minutes Later… The morning…

I Had an Accident, Had to Be Casted and Bedridden. My In-laws Went on a Vacation and Left Me Behind. When They Came Back…/th

I Had an Accident, Had to Be Casted and Bedridden. My In-laws Went on a Vacation and Left Me Behind….

Coming Home to Take Care of My Sick Father, My Husband Hired a Shipper to Send My Luggage with a Note: “Don’t Come Back!” — 30 Minutes Later…/th

Coming Home to Take Care of My Sick Father, My Husband Hired a Shipper to Send My Luggage with a…

InLaws laugh as they gave her the Rusted van as her inheritance, — Unware the van was made of gold/th

InLaws laugh as they gave her the Rusted van as her inheritance, — Unware the van was made of gold/th…

They Forced Her to Marry a Sick Man So He Could Die in Peace—But What She Did Next…/th

They said he wouldn’t live past the year, so they gave him a wife. Not out of love, but to…

They Laughed When She Was Forced to Marry the Village Madman—But What He Did After the Wedding…./th

They Laughed When She Was Forced to Marry the Village Madman—But What He Did After the Wedding…./th emily was called…

End of content

No more pages to load