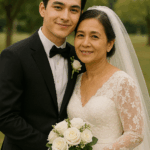

Marrying a Woman 25 Years Older – On Our Wedding Night, She Knelt and Begged for Something That Horrified Me/th

I was 20 years old when I agreed to marry a 45-year-old widow, simply thinking it was a way to repay her. She was gentle and discreet, and had once helped me when I had nowhere else to turn. I thought living with someone so experienced would be peaceful. But then, on our wedding night, before I even had a chance to touch her, she knelt down, held my hand, and in a trembling voice said, “You just have to promise me one thing, only one thing.” And that one thing changed my entire life.

Why would a woman who had lost her husband take the initiative to marry a young man like me? And in the end, was I truly her husband, or simply a part of some frightening plan that had been laid out long ago? I once thought I would marry a girl my age, or at most a few years older—someone youthful, a little free-spirited but caring.

Not someone like Ms. Dung, a 45-year-old woman, widowed for the past seven years, exactly 25 years older than me. When she proposed marriage, I thought I had misheard her. Her eyes were calm, her voice neither high nor low, even slightly husky, as if discussing a business matter: “If you have no one else, then be my husband.”

I stared at her for several seconds. I had worked in her household for nearly two years, staying there when I had nowhere else to go. She did not treat me warmly, but she was never cruel—never insulting or bossy. She always kept her distance: polite but cold. I laughed, thinking she was joking.

“You’re serious? I’m still young to be getting married.”

“So what if you’re young? The person who lives with me doesn’t need to be older—just needs to keep their word.”

I fell silent. At that moment I thought about the two years I had sat under her porch, eating leftovers from her meals. I thought about the times when I lay sick with a fever, and she would simply leave some medicine and a warm towel. She didn’t ask many questions, didn’t comfort me—just left them there and walked away.

She didn’t need me to love her, only to nod my agreement. And I nodded—not out of love, but because I felt I owed her. The wedding was not grand: no relatives, no banquet tables. She said to keep it simple, mainly for the paperwork. “We don’t need anyone to understand—only we need to understand.”

On our wedding day, I wore a suit she had personally measured and ordered for me. She wore a black velvet áo dài, her hair in a low bun, no makeup. As we stood before the altar burning incense for her late husband—a man I had never met—I glanced over and saw her hands tremble slightly. She didn’t cry, but I knew she was holding something back.

That night, I stepped into the bridal room with my heart uneasy and my mind blank. Everything had happened so fast that I hadn’t even managed to call her “wife” properly. The room had only a large white wooden bed—no flowers, no candles. Next to it was a simple dressing table and a dim yellow night lamp. She sat on the bed, hands on her lap, her posture straight like someone awaiting judgment. I stepped forward cautiously, and she looked at me and softly said, “Sit down.” I sat on the edge of the bed. The atmosphere at that moment was so strange.

There was no laughter, no pounding heartbeat—only something suffocating, like a storm about to hit, and I was the one completely unaware. She suddenly stood up, walked toward me, then knelt down. I panicked.

“Hey, what… what are you doing? Please, get up.”

But she didn’t. She just took my hands—ice cold, though the air conditioner wasn’t even on.

Her voice trembled, but her eyes kept staring straight into mine. “I just ask you one thing, only one thing.”

I was flustered. “Okay… tell me. But you have to stand up first.”

“No. You have to promise me first, then I’ll stand up.”

I nodded just to get it over with. “Alright, I promise.”

“Promise me you will never ask about the last room at the end of the hallway on the second floor. No matter what you hear or see, don’t open the door, don’t ask, don’t mention it—can you?”

I widened my eyes, my head spinning.

“What are you talking about? Is there something in there?”

She gripped my hand so tightly it hurt. The look in her eyes at that moment was something I had never seen in anyone before—fear and authority mixed together, as if she was trying to control me.

“I told you, don’t ask. Just promise.”

A chill ran down my spine, but I nodded—not because I believed her, but because I knew that if I refused, the night would not end peacefully.

She stood up, without smiling, without another word, and lay on the bed, turned to face the wall. I sat there, my whole body cold, not daring to touch her, not daring to turn off the light. I didn’t know when I fell asleep—perhaps I only drifted off from exhaustion.

But I woke up at 2 a.m., not from cold, not from a nightmare, but from a scream—a woman’s scream coming from the second floor.

“No! Don’t! Don’t come near me!”

I shot up as if yanked by an invisible force, my heart pounding. I looked beside me—she was still lying there, eyes open, staring straight at me, calm as if she had never been asleep.

The next morning, I woke up in a half-dazed state, sunlight streaming through the white curtains onto the polished wooden floor. I turned to the side, but Ms. Dung was gone.

The blanket was neatly folded, the pillow without any crease, as if she had never slept there at all. I sat up, the scream from the night before still echoing in my mind. That scream had sent shivers through me, my heart racing. I told myself maybe it was a dream—but the image of her lying with her back turned, eyes wide open, silent… that was definitely not a dream.

I went downstairs barefoot. The smell of plain rice porridge rose up, mixed with the faint scent of pandan leaves, making my stomach growl instinctively.

Ms. Dung was standing at the stove, stirring the pot, her posture perfectly straight, her hair neatly tied with not a single strand out of place. She heard my footsteps but didn’t turn around, just said, “You’re up? Go wash your face, I’ve made porridge.”

I sat at the table, quietly watching her. She radiated a calmness, as if nothing unusual had happened the day before—no so-called wedding night, no kneeling request, and no scream in the night.

I spoke, my voice cautious. “Did you… hear anything last night?”

She didn’t answer, just ladled the porridge into a bowl, placed it neatly in front of me, and only then spoke—slowly, clearly: “The porridge is still hot. Eat.”

And that was all she said.

That sentence made me too afraid to ask any further. I kept my head down, eating the porridge, my mind hovering over the question—was she avoiding it, or had she really not heard anything?

After the meal, while I was washing the dishes, she sat down on a chair, still slowly drying a towel in her hands, then suddenly said, “From today on, you are not allowed to leave the house after 7:00 p.m., understand?”

I turned my head. “Why? Is this area unsafe or something?”

She didn’t look at me, just kept drying the glass, her voice steady: “It’s not safe. And besides, I don’t like it. The night is for resting, not for wandering around. Having me is enough for you.”

I nodded, though feeling a bit uneasy inside. Just yesterday I had been free, and now it felt like I was being kept under house arrest. Still, I forced a smile, trying to appear agreeable.

“Alright, I’ll try to arrange things so I can go out earlier if needed.”

I thought that was the end of it, but before I could breathe a sigh of relief, she continued:

“And your phone—leave it in the living room. You’re not allowed to bring it into the bedroom, and you’re not allowed to make calls after 8:00 p.m. Nighttime is for sleeping, not for chatting or fiddling with your phone.”

I froze. The tone didn’t sound like advice—it sounded like an order.

Quietly, I said, “I have friends… sometimes I need to make a quick call.”

She lifted her head, and the eyes that had been avoiding mine suddenly locked onto me. “Friends? At your age? You’re my husband now—you’re not some kid loitering around on the streets anymore. I want everything in this house to be quiet, clear, and orderly. Do you understand?”

I gave a strained smile and nodded, but inside, something felt strange. The way she called me “some kid loitering around” sounded both mocking and pitying. And the way she said “my husband” felt more like a title than a real emotion.

That afternoon, when I was bringing in laundry from the yard, I accidentally saw a nameplate in front of a room on the second floor. It had just one word on a white background: “Trí.”

I stared at that nameplate for several seconds, feeling something heavy—not curiosity exactly, but a strange weight in my chest.

That evening, while we were sitting together peeling fruit, I tried asking gently, “Dung, who is Trí? I saw the nameplate on the second floor.”

She was peeling an apple, and her hands stopped mid-motion. After a moment, she set down the knife and turned her whole body toward me.

Her eyes were cold—angry and wounded, as if someone had just ripped open an old scar. “I told you not to ask. Don’t you remember?”

I quickly explained, “Oh, I didn’t mean to… I was just hanging the laundry this morning, and I looked up and saw the name, so I was curious.”

“Curious about what? What’s there to ask? I don’t want that name mentioned in this house. If you ask again, I’ll throw you out.”

I froze. She had never raised her voice at me before, never used the word “throw” toward me. I stared at her—not because I feared her words, but because of how she said them. Her voice trembled slightly, her lips pressed tightly together, her eyes reddened but no tears fell—as if she felt both hatred and deep pain.

All I could do was stammer, “I… I’m sorry. I won’t ask again.”

She stood up without a word, walked straight upstairs, each step landing like a hammer on my chest.

That night, I lay alone, staring at the ceiling, realizing that I was neither a husband nor truly part of the family. I was just someone brought in to sign marriage papers, only to live within a framework where I could not ask, could not leave, and could not fully understand.

I had once thought marrying an older woman would be a safe path—no petty conflicts, no financial pressures, none of the unreasonable sulks of same-age relationships. Yet after just one week in that house, holding the title of legal husband, I began to feel no different from someone under surveillance.

It all began one evening when Dung said she had a headache, her voice so soft it was almost on the verge of tears. “My head hurts a lot, but we’ve run out of medicine at home. Can you go buy some for me?”

I looked at the clock—it was close to 8 p.m., but still not too late. “Sure, I’ll go right now. There’s a new pharmacy nearby that’s open until 10.”

She said nothing, just handed me the money.

I stepped out the door, thinking nothing of it. But I had no idea that such a small act would become the excuse for an even stricter chain of control.

When I returned, the bag of medicine still warm in my hand, the lights in the house were still on.

I stepped inside, barely taking off my slippers when I heard the slap-slap of other slippers coming down the stairs. Dung appeared. Her face was pale white, her eyes bloodshot as if she had just cried, and her mouth carried no hint of a smile. She stood blocking the way, then suddenly said loudly,

“How many times have I told you not to leave the house at night? Don’t you remember?”

I froze, needing several seconds to realize she wasn’t joking.

I raised the bag of medicine, trying to keep my voice calm.

“I only went out to buy you medicine. You were the one who asked me to go just now.”

She didn’t answer. She stepped forward, snatched the bag from my hand, glanced at it quickly, and put it on the table. Without another word, she reached into her pocket and took out a small key, then headed upstairs.

Before I could react, she returned holding a small black device with a fingerprint scanner. She attached it to the doorknob of my room and stood there, not looking at me, her voice sharp as a blade.

“From now on, if you want to go into your room, tell me. I’ll unlock it for you.”

It was only at that moment I realized I was no longer the owner of the room I slept in. And this house—this house was no longer a place I could freely come and go.

Over the next few days, I tried to live silently, like a shadow. I told myself she was just stressed and that it would pass. But things only grew stranger.

One afternoon, while reading in the living room, I accidentally spotted a tiny camera hidden cleverly in a potted plant hanging from the wall. I hadn’t planned to make a scene, so I asked lightly, as if joking,

“Hey, Dung, did you install cameras in the house?”

She was peeling an orange and looked up very slowly, speaking evenly.

“Yes. I installed them a long time ago, even before the wedding, because I was afraid of burglars. Big house, just me living here.”

I pressed my lips together.

“Right.”

“Though I thought you’d assume I put them there to watch what you’re doing.”

She set down the knife and sat up straight.

“If you’re not doing anything wrong, why be afraid of a camera?”

I swallowed hard. That line hit right at the suffocating feeling I’d been trying to swallow since stepping into this house. I could only force a smile.

“Right. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

But inside, I was freezing—freezing from her gaze, from the way she always justified her control with reason. Freezing until it felt like I was living in some kind of silent psychiatric ward, where every movement was secretly monitored.

And the control didn’t stop there—it started turning bizarre. In front of outsiders, Dung would sweetly call herself my “older sister” and refer to me as “my husband” like a pampering wife calling her younger spouse.

But in the house, she called me differently:

“Where’s that boy? Tell him to come here.”

“Eat faster.”

“Don’t sit there dawdling like a kid.”

“If you stay up late, I can’t sleep. Go to bed now.”

I used to stay calm, thinking maybe she just wasn’t used to living with someone else. But no—the more silent I was, the tighter she held on. As if controlling me was the only way she could feel safe.

I wanted to leave many times, but where could I go? The marriage papers were real. None of my friends would believe me. They’d tell me I was lucky—married to a wealthy woman, with a house to live in, money to spend, no hard life.

Who would believe a 20-year-old guy was being locked up by a wife over 20 years older?

I once told a close friend over the phone,

“I feel like a ghost in this house. I don’t dare speak, don’t dare breathe too loud. Whatever she does to me, I can’t react. I have zero freedom. I’m alive but have no rights at all.”

My friend laughed.

“You’re living the good life and still complaining? Your wife runs a whole big factory. Just put up with it.”

I said nothing more, just hung up and lay still in the dark. The room lights were off, but I knew there was a tiny camera watching me.

And the scariest part wasn’t being recorded—it was not knowing how long I would be recorded for.

I had thought that house only had two people—me and Dung—a sealed-off world where I lived like a shadow under strange rules and watchful eyes.

But I was wrong. Things hadn’t stopped there.

That day, it rained—a heavy, pouring rain from early morning.

I was in the kitchen chopping onions when I heard the sharp clang of the iron gate swinging open — an unusual sound, since ever since the wedding, no one had come to this house except me and her. I put the knife down and hurried to the door.

A young man stood there, his dark shirt soaked through with rain, one hand pulling a suitcase, his expression cold as ice. He stood squarely at the porch, without knocking, without asking permission.

I spoke first, politely.

“Excuse me, who are you here to see?”

He looked me up and down, his gaze cold and sharp, like he was staring at a stain on spotless tile. The corner of his mouth curved into a half-smile, his voice dripping with mockery.

“And who are you to ask?”

I stiffened, about to answer, when Dung’s voice came evenly from behind me.

“Trí, you’re back?”

I turned. She was standing on the step, hands still dusted with flour — probably from baking. But her face showed no joy, no surprise — only the look one gives to an uninvited guest.

The young man gave a cold laugh.

“Back, yeah — back to see what other nonsense my mother’s gotten herself into.”

He glanced at me, his tone biting.

“You’re just the guard dog for my mother, aren’t you? How much do you get paid a month?”

The words stunned me. I froze, feeling the blood rush to my face. I had never been insulted so brazenly — especially in the house where I was supposed to live as a lawful husband. My hands clenched as I tried to stay calm, but I couldn’t swallow it anymore.

I answered, my voice tightening.

“You have no right to talk to me like that. I’m Dung’s husband. If you don’t like it, just say so — but don’t insult me.”

Before I could say more, Dung rushed down the step, her voice hissing.

“Shut your mouth! No one gave you permission to speak to him like that. He’s my son.”

I turned to look at her, and her eyes made me shiver — not with anger, but with a kind of unhinged confusion I had never seen in her so clearly before.

“You’re scolding me?” I asked, my throat tight. “I don’t need you to defend me in that… domineering tone.”

She snapped back, then turned to Trí.

“And you — don’t you speak like that in this house. He’s my husband, with a legal marriage certificate.”

Trí laughed — a laugh thick with contempt that rang through the house’s usual silence.

“A marriage certificate? You married a guy five years younger than your own son, and you’re waving that paper around to claim the house?”

I looked at her, waiting for an explanation, some defense — but she stayed silent. She neither stood by me nor said anything to Trí. She simply turned and walked back to the kitchen, as if nothing had happened.

From that moment on, I became an excess object in the very house where I lived.

Trí walked in as if he owned the place — and perhaps he did. He knew exactly where everything in the house was kept, even the code to the safe in the study. I sat still, not daring to ask, not allowed to ask.

Dung was quieter than ever. At dinner that night, no one spoke to anyone. The only sounds were the clink of chopsticks against bowls and the occasional smacking of Trí’s lips.

“Not bad. Haven’t had salted fish like this since Dad was alive.”

Dung’s chopsticks tightened. Though she kept her head down, I saw her wrist tremble slightly.

I tried to keep my distance, keep respectful — but I was caught between them: one who always saw me as something disposable, and one who had never truly treated me like family.

That night, I lay facing the wall, listening to Trí’s footsteps pacing the hallway. Each step was a tight pull in my chest.

I asked myself where I stood in this house — a husband, a guest, or some kind of object Dung needed for a purpose I still didn’t know.

I used to think the control in this house stopped at the cameras, the curfew, or needing permission to enter my own room.

But I was wrong — everything was only just beginning. After Trí, Dung’s son from her previous marriage, came back, the air in the house grew heavier. Trí no longer argued with me, but every step he took, every glance he cast, carried undisguised contempt. I tried to ignore it. I thought if I stayed silent, things would be peaceful.

But I didn’t expect that the fear in this house wouldn’t come from Trí — it would come from the very woman who had married me.

That night, just as I had turned off the light to go to bed, I heard a gentle knock on the door. The knocks were slow and even, as if someone didn’t want to wake me but wanted me to know they were there.

I switched on the light and stepped out. The door was slightly open. Dung stood there, holding an old notebook wrapped in red cloth, her voice quiet but clear:

“Come to the living room for a bit, I need your help with something.”

I didn’t dare refuse, though a faint unease stirred inside me. I followed her.

The tea table was already set — a cup of warm water, an incense stick half burned, and a book opened neatly as if waiting for someone to read.

She handed me the cloth-wrapped notebook, pointing to a section written in careful handwriting — probably hers.

“Read this part slowly. Pronounce every word clearly.”

I took it. My eyes skimmed over strange lines, sentences without a clear subject, like a chant blending ancient phrasing with everyday language.

I asked quietly, “What is this?”

She sat upright, her eyes fixed on every change in my expression.

“It’s for keeping peace. Reading it alone isn’t enough — I need someone to read it with me. You don’t need to understand it.”

“I don’t need to understand? Just read it?”

“Yes. Just read it, that’s enough.”

I scratched my head, still hesitant. Before I could say anything, her voice sharpened for the first time that night, her tone rising noticeably:

“Read it. If you don’t, I’ll be cursed.”

I flinched — not from her tone, but from her reddened, tear-filled eyes, like someone facing a nightmare no one believed in.

I swallowed hard and began to read. Each word that left my mouth felt dry and cold, and it was as if the room itself was being drained. The incense burned slowly, releasing a sharp, acrid scent that stung my eyes.

She sat across from me without blinking. When I finished, she slumped back into her chair, her voice dropping:

“Good. Today’s fine.”

I asked, “Do you really believe in this?”

She lifted her head, and for once there was no coldness — only a rare mix of confusion and fragility.

“You don’t know. After Trí’s father died, I went everywhere. Everyone said I’d been tainted with yin energy. They said if I didn’t have a young man by my side, I wouldn’t live past fifty.”

I froze — not because of the superstition, but because she said it with a seriousness as if it were absolute truth.

I stammered, “So you married me because…?”

She didn’t answer right away. She lowered her head, then slowly said,

“I needed you here. I didn’t mean to use you… but I needed someone to balance things.”

“Balance what?”

“Balance the energy. Balance yin and yang. You’re young, and your age fits mine.”

Her words rang in my head like a hammer. My back turned cold. My hand still held the notebook, but it felt heavy as stone. I lowered my head and said nothing more.

That night, I went back to my room and curled up like a child. I didn’t dare sleep — not because I was afraid of being harmed, but because I had begun to fear the absolute, stubborn, and distorted belief in Dung’s eyes.

From that day on, it was the same every night.

Exactly at 10 o’clock, she called me to the living room. I read, she listened. At first, I hesitated, but later I read like a machine—without thinking, without resisting. She only said one sentence, but it still haunts me to this day:

“I know you don’t believe, but whether you believe or not, you still have to read. If I collapse, the first one to be dragged down will be you.”

I don’t remember exactly when I began to change—whether it was when I was forced to read the chant every night, or when I started reading without looking at the words, only listening to the sound of Dung’s breathing behind me. Everything slid past me like a dark dream, and I quietly sank into it without daring to ask why.

Until one afternoon, when the sunlight from the window stretched pale yellow across the floor—silent and weary—Trí unexpectedly knocked on my door. It was the first time he had sought me out since returning home. I was stunned.

Before I could react, he pushed the door open and let out a curt but razor-sharp sentence:

“Come with me. We need to talk.”

I studied his face, but he didn’t look back at me. He turned and strode down the stairs. I only had time to grab a thin jacket before silently following him.

Trí led me to a small café by the edge of the lake. The place was quiet, only the creak of the ceiling fan and the occasional breeze rustling through the leaves. He chose a table in a secluded corner, sat down, crossed his legs, and pulled an old, frayed leather notebook from his backpack.

He placed it in front of me, his voice lower, stripped of his usual defiance:

“Read it. It was my father’s.”

I flipped through the first pages, the handwriting slanted, with an urgency in the hastily written lines. Despite trying to stay calm, my hands trembled slightly when I reached the first entry:

Dung says I’m being followed by a spirit. She insists we must perform a ritual, seal the dragon vein, to protect the family estate. I don’t believe it, but she cries, saying if I don’t do it, I’ll lose everything—house and children.

I froze, looking at Trí. He took out a cigarette, didn’t light it, just held it between two fingers and murmured:

“My father was a construction engineer—stubbornly rational—but because of my mother, he started to fall apart. He began believing in superstitions, going to temples every week, moving into a separate bedroom… and saying there was something very cold in the house.”

I swallowed hard, my voice hoarse.

“And then what happened?”

Trí leaned back in his chair, eyes distant. His tone was steady, but there was something tightly restrained beneath it.

“He killed himself. One day, I came home and found him hanging in the last room on the second floor. No suicide note—only this notebook left on the desk.”

He pointed to the last line, the handwriting shaky and uneven:

I don’t know if I’m losing my mind, but I’m certain of one thing: Dung believes in it so much she’s willing to give up everything… including me.

I sat frozen. The air around us seemed to congeal. Inside me, the vague fragments of the past weeks began to fit together: the midnight chants, the pleading look in Dung’s eyes, the screams from the second-floor room, and the way she looked at me—not like a wife at her husband, but with an obsessive, dependent, invisible expectation.

My voice cracked:

“Why are you telling me this?”

Trí looked straight at me—not with contempt, not with coldness, but with a bare, blunt truth:

“You’re the next substitute. Don’t you see? You’re taking my father’s place—reading chants, kept in the house, living like a man raised in a cage. That’s not a marriage. That’s a kind of sacrifice.”

I wanted to argue, I truly did—but no words came. Because every word he said, I had already felt in my own skin.

Trí went on, his voice low but certain:

“I didn’t stop you from marrying my mother because I thought you were the one who wanted it.”

But every night, seeing you sit there reading those chants like a puppet, I knew you weren’t the mastermind—you were the victim.

“So what should I do now?” I asked, my voice so small it barely felt like mine.

“Ask yourself this—if you can’t get out, sooner or later you’ll leave that house wrapped in a white shroud.”

That night I came home half broken, half awakened.

Everything Trí had said—the diary pages of a dead man, and Trí’s knife-sharp gaze when he said You’re the next substitute—kept circling in my head like the clanging of a bell beaten endlessly by the wind.

The moment I opened the door, I saw the same scene as every other night:

The tea table set, the pale yellow lamp casting its light over the teapot and cups, an incense stick half-burned in the censer, and on the table—the infamous red-covered book—open to the same page, as if there had never been a single interruption.

Dung sat there, straightening the tablecloth, her voice light but tinged with anticipation:

“I’ve made the tea. Come in and read.”

I stood frozen at the doorway, my hand still gripping the cold iron doorknob, my palm slick with sweat. I didn’t answer. I didn’t step forward.

After a few seconds, I turned and walked straight upstairs, each step heavy as stone.

Behind me, her voice rang out—for the first time in months, sounding almost like pleading:

“If you stop halfway, I won’t be able to take it.”

I stopped on the fifth step, without turning around, without replying.

My back was tight, as if something was pulling me backward, but my legs kept moving.

That night, I didn’t go down, didn’t read, didn’t explain. I chose silence as a way of cutting the cord.

The next morning, Trí arrived earlier than usual. He didn’t bother knocking.

Dung didn’t come down to greet him. I opened the door.

He looked at me for a moment, then spoke in a low voice:

“Get ready—we’re going to see a doctor today.”

I didn’t ask anything more. We took a taxi to a small private clinic.

The doctor was an elderly man with silver-rimmed glasses and a steady, probing gaze. He spoke little. After glancing over the file, he turned to Trí:

“She’s your mother, right?”

“Yes, my mother.”

“I remember her. More than ten years ago, she came here many times. Her problem is her belief—and the distortion in how she explains all her pain.”

I cut in, hesitating:

“Doctor… is she actually mentally ill?”

He looked at me—not coldly, but with a strange kind of compassion.

“Not insanity—delusional disorder after psychological trauma. She believes she’s cursed—that only by having a young man beside her can the yin energy be kept from pulling her into the abyss. If not, she believes she’ll lose her mind… and drag down anyone close to her.”

I sat in silence. Each word the doctor spoke felt like a small knife cutting into my memories:

The pleading look in Dung’s eyes on our wedding night… her nightly whispers at the tea table… and the nightmares she never told in full.

Trí handed me the file and together we wrote a formal report to the authorities.

I described everything—my phone confiscated, my movements restricted, being forced to read chants, being coerced and bruised. In one night, I refused.

Everything I had once endured, I wrote down line by line—slowly and clearly, as if facing myself for the first time.

Three days later, the police came to the house.

I was in my room when I heard the hard knock at the door, and Dung’s voice calling out loudly:

“Who is it?”

“We’re from the authorities—there’s a report requiring an inspection.”

She opened the door, and when she saw me standing beside them, she stepped back, her face pale, her lips pressed tightly together.

I looked at her and said softly, “I’m sorry, but I can’t live like this anymore.”

The officer read the warrant. One of the team members pulled the inspection order from a file.

“We have received a report of unlawful confinement, psychological control, and invasion of personal privacy. Please cooperate.”

Dung gave a slight nod, her body sinking faintly, but her face showed no reaction. A silence so thick it seemed to press down on the air filled the house. They began searching each room—from the living room, to the kitchen, then upstairs.

When they entered my bedroom—the place where I had spent months living like someone under house arrest—it took them less than two minutes to find the small camera hidden in the corner of the wooden cabinet, wedged between a plastic flowerpot and the curtain.

Another officer unlocked Dung’s personal wardrobe with a fingerprint scanner. Inside, my phone lay there, battery removed, SIM card gone—who knows since when.

I stood still. Part of me wanted to speak, but my throat tightened. My hands hung loosely at my sides, unconsciously clenching when another officer asked, “Can you show us your injury?”

I raised my right hand. Around my wrist, a dark blue-purple bruise stretched down to the bone—marks left from the grip of a hand on the night I refused to sit down and read the familiar chant. The officer bent down to photograph it, his voice serious but measured:

“Injury evidence, recorded for the coercion case file.”

It all took barely twenty minutes.

No shouting. No tears. Only Dung, standing there, her back lightly against the wall, one hand resting on her stomach, eyes fixed on some far-off point.

When they announced the decision to escort her for mandatory evaluation, I thought she might lash out—or at least protest. But she didn’t. She only turned her face toward me, the motion slow and heavy, as if dragging decades with it.

Her eyes were rimmed red, the lower edges glistening but no tears falling. Her voice came out hoarse and cracked, like someone’s throat was being squeezed:

“You know? I can only sleep peacefully if you have dinner with me every night.”

She paused, drew in a breath, then continued—softer, but more desperate:

“Now I guess that dream will haunt me again.”

No one spoke. Trí kept his head down, looking neither at me nor at his mother. I could only stand there, my chest weighed down—half as if I’d finally been freed, half as if I’d just pushed someone into the darkness they’d always tried to hide.

But I knew I had no other choice. I didn’t answer. Trí stayed silent. Two men—a son and a husband—unable to say even one word of farewell.

I stood and watched them take her away. My mind was empty, my heart not aching but stretched, as if a cord that had bound me too long had finally been cut. And I knew that from that moment on, I had brought everything into the light—even if that light might sting the eyes of those who’d lived too long in the dark.

From the morning Dung was taken away, the house became empty—in every sense of the word.

There were no people left, and no warmth. I didn’t stay another night there.

I didn’t pack much—there wasn’t anything I felt the need to keep. The room where I used to sleep every night now held only the hard wooden bed and a red-covered land certificate, closed and lying silently in the drawer.

I moved back to the old boarding area where I’d lived before stepping into the life of a woman in pain—a woman I once thought was my benefactor, then became my wife, and in the end, the person whose truth I had to drag into the light.

On my first day back at my old carpentry workshop, I noticed the looks from people around me were no longer the same. Not quite welcoming, but not hostile either—just curious, tinged with disdain.

During the lunch break, I overheard a small group huddled near the fan, whispering:

“That guy, yeah, the one who married that 45-year-old woman—heard he got caught gold-digging and ran away. The type who clings to women for support and then ends up back as a laborer—pathetic.”

I heard everything, but I didn’t react.

Not because I accepted it, but because, after everything, I was too used to people judging an entire story from its surface.

A week later, the case made it into the papers. A few small outlets ran blunt headlines:

“45-year-old woman marries younger man, sent for compulsory psychiatric treatment after using talismans to bind his life.”

At first, I thought the news would sink unnoticed. But, unexpectedly, social media reacted differently. I read the comments:

“So that’s how it was… She looked so gentle; who’d have thought she lived like that?”

“Poor guy—only 20 and dragged into that mess.”

“Let’s not blame anyone; maybe she suffered a lot before and that’s why she became like that.”

For the first time, I saw strangers believe me, even though they’d never met me.

And for the first time, I realized justice doesn’t always come from the courts—it can come from the clarity of strangers’ eyes.

As for Trí—after that day, he neither called nor texted me. The silence stretched on, as if we’d once been on the same front, and now, having completed the mission, each returned to our own life. I didn’t blame him. I knew everyone has their own way of facing pain, and that despite his hardened exterior, he was still a son.

An old friend who worked at the psychiatric hospital told me: Trí still visited his mother regularly—always staying exactly an hour, saying little, leaving without a word. I wasn’t surprised. I just smiled faintly and said, “Maybe there’s something in his heart he still can’t name.”

People asked me if I regretted it. I never knew how to answer briefly. What I went through wasn’t just a failed marriage—it was a chapter in my life. A slice of time where I was forced to grow up, to face the truth, and to choose between keeping silent for peace or hurting someone to protect myself.

I’m no longer afraid of marriage. I just understand better the price of a bond not born from love, but from wounds and misplaced trust.

I remember a night not long ago when Dung whispered to me:

“You’re my savior—thanks to you, I can go on living.”

Now, when I hear those words again in my head, I don’t feel warmth. I feel something misplaced. Because a savior is someone who gives, yet in this story, I was the one being held—not to be loved, but to balance a warped belief.

Even now, I don’t call it a mistake. I don’t feel hatred for anyone. I tell it only so I can understand who I once was, why I stepped into it, and why I had to walk away.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that I once thought marrying someone older meant stability. But this story taught me that age doesn’t determine maturity—and unhealed wounds can turn a person into shackles for someone else.

Sometimes, we enter a relationship not out of love, but out of gratitude, responsibility, or simply because we feel we should. But pity can’t save a broken soul. And silence is not always gentleness—it can be the way we enable a greater tragedy.

We all carry wounds. But if they aren’t healed, they will hurt not only us, but the innocent people around us.

News

My Mother Came from the Countryside to Visit, but My Mother-in-law Scolded Her: “Go Eat in the Kitchen” – I Did Something That Left Her Stunned/th

My Mother Came from the Countryside to Visit, but My Mother-in-law Scolded Her: “Go Eat in the Kitchen” – I…

A nurse slapped the dead wife of a millionaire… and the reason surprised everyone./th

In the early morning, in the most luxurious hospital in the city, I looked at the body—supposedly the wife of…

The poor Black maid stole the millionaire’s Ferrari for a completely unexpected reason./th

The poor Black maid stole the millionaire’s Ferrari for a completely unexpected reason.The action she took left everyone stunned. Grace’s…

Poor Rancher Married Fat Stranger for a Cow — On Wedding Night, She Locked the Door/th

Poor Rancher Married Fat Stranger for a Cow — On Wedding Night, She Locked the Door/th Thomas Murphy never thought…

“Don’t go to your husband’s funeral. Check your sister’s house…”/th

Don’t Go to Your Husband’s Funeral. You Should Check Your Sister’s House. She Received… That morning, the day of Patrick’s…

A Rancher Finds a Young Woman with Two Newborns in His Barn… and Everything Changes Forever/th

A Rancher Finds a Young Woman with Two Newborns in His Barn… and Everything Changes Forever Chapter 1: The StormMauricio…

End of content

No more pages to load