The family brought my grandmother’s coffin to the crematorium; the staff reported that the fire went out three times in a row – when they opened the furnace to check, they were horrified…

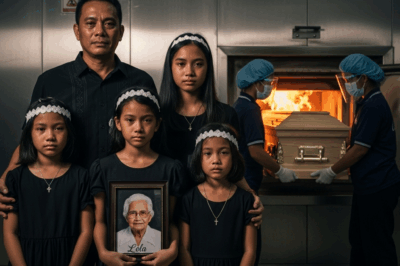

My grandmother’s funeral took place on a gray morning, with a light drizzle. She had died suddenly, quietly like a breath fading away: no illness, no last words. We were all devastated, especially my father, her youngest son, who had been with her until the very end.

After the ceremony, we brought her to the city crematorium. The coffin was placed into the furnace; incense spiraled in heavy clouds. We waited in silence in the hall, each heart weighed down.

Fifteen minutes later, a crematorium worker entered with a confused face:

—“Please forgive us… but the furnace just suddenly shut down. We’ll restart it right away. It may be a technical fault…”

We nodded, thinking it was a mechanical issue. But then it happened a second time… and a third… exactly the same. The fire flared up and then died out. The system stopped halfway, showing no clear error. The technician was bewildered; he had never seen a malfunction repeat so many times.

Finally, the chief operator —a man with over twenty years of experience— decided to open the chamber to inspect it. His face turned strange… pale, with a flicker of fear. And then…

When the chamber door opened… all the employees froze.

Inside, there was no body turning to ashes.

My grandmother was sitting up.

Her eyes were wide open, glassy, yet glinting with resentment. Her lips moved… as if speaking… but no sound came out. The body, which should already have been cold, trembled slightly.

One worker screamed in panic:

—“She… she’s not dead! SHE’S ALIVE!”

Our whole family rushed in. My father collapsed to his knees, crying out “Mama!” like a child. They called emergency services at once, but all were helpless: there was no pulse, no reflexes. And yet, the body wasn’t stiff, and her mouth kept faintly moving.

One nurse whispered:

—“The old woman’s body won’t burn… something is preventing the fire from catching… as if… an invisible force is stopping it…”

Then the technician, trembling, muttered softly:

—“I saw this once… twenty years ago… also an old woman… she too sat up in the furnace… and afterward, her whole family… fell into misfortune…”

Everyone was struck silent.

My grandmother didn’t awaken, but she wouldn’t burn either. Each time the flames reached her coffin, they went out. We had no choice but to bring her back home, in the soot-blackened but still intact coffin.

From that day on, strange things began to happen…

Ever since we brought her back, a fine mist seemed to hang in the house. The incense smoke flickered: sometimes flaring up, sometimes dying as if blown upon. The wall clock, which had worked fine, stopped at 3:15; whenever rewound, the minute hand insisted on returning to that mark. Each night, the striped cat in the yard sat before the coffin, fur bristling, growling deep.

On the second night, my father dozed in a chair beside the coffin. He woke with a start at the sound of clinking, like a spoon tapping porcelain in the kitchen. He followed the sound; suddenly, the oil lamp lit with a sharp paf!; the flame, greenish-blue, rose straight like a spear. Before his shivers eased, he heard my grandmother’s voice —thin as smoke, but clear:

“Do not burn me. Take me back to the village, to rest beside him. Open my clothes, there is a key.”

Shaking, my father ran to wake everyone. My elder sister and I held him; our youngest aunt grabbed a flashlight. My sister-in-law —who had dressed Grandmother in her burial clothes— said hesitantly:

—“I put another layer of clothing on her, so she wouldn’t feel cold… I didn’t see any key.”

We all leaned over the coffin. With trembling hands, my father unfastened Grandmother’s inner blouse. At the edge of the lining, in a seam stitched shut as if never touched, was a small knot. With scissors, he carefully opened it: out fell a bundle of rusty keys tied with a faded red string, and a small brown cloth pouch, sewn shut. Our youngest aunt bit the thread open: inside was a sheet of paper folded four times and a polished bodhi bead.

The paper bore my grandmother’s handwriting —slanted, even, the violet ink faded:

*“He and I promised: whoever leaves first shall rest beneath the starfruit tree, behind the house. I fear you may be too busy and send me to the crematorium. I carry an amulet that ‘forbids fire,’ given to me by a monk from Yên Tử during troubled years —it protects me from fire misfortune. With this amulet, the flames will not take. If you wish to cremate me, remove the amulet and lay me to rest beside him. Do not send me far from my land.

—Your Grandmother.”*

We all looked at each other, goosebumps rising. My youngest aunt burst into tears:

—“In my rush… and fearing she’d be cold, I dressed her in extra clothes… everything was so hurried, I didn’t know…”

My father clutched the coffin, weeping like a child. He begged his mother’s forgiveness; he said, blinded by life’s rush, he had forgotten what she always repeated: “Live in harmony, die in peace.”

The next morning, the crematorium technician came to light incense. Hearing the whole story, he sighed:

—“Twenty years ago I saw another grandmother like this. When her family buried her beside her husband, all was at peace. That ‘fire-forbidding’ amulet —I dare not judge if it is real, but sometimes a departing soul’s last will is stronger than any button or flame.”

Our family decided to hold a ceremony of apology at home, invite a monk to recite sutras, remove the bodhi bead from Grandmother’s clothes and place the amulet on the altar. At noon, the drizzle ceased; a thin ray of sunlight pierced the eaves, dust floated like gold. The wall clock, which had stubbornly returned to 3:15, began ticking normally again.

That afternoon, we brought her back to the village: the road smelled of straw and earth; the starfruit tree behind the house was heavy with fruit; the neighborhood children laughed. My mother scattered salt and rice; Sixth Aunt walked ahead with a bundle of incense. As soon as the coffin crossed the yard, the air filled with the scent of ripe starfruit; the cat stopped growling and stretched in the sun on the step. With trembling hands, my father laid her beside my grandfather, right in the shade of the tree.

That night, we kept vigil in the yard. No more clinking sounds, no stopped clocks. My father lifted a cup of tea, gazed at the starfruit tree, and whispered softly:

—“You’re home now, Mama.”

On the twenty-first day, we held the rites. The technician returned, smiling:

—“This time I come with congratulations: the furnace no longer ‘breaks down.’ Sometimes even machines feel fear.”

He lit incense, murmured prayers, and left. Watching his figure go, Sixth Aunt sighed:

—“The living think we control everything. Until the flame won’t catch, and then we remember that promises… and wishes… exist.”

On the forty-ninth day, the sun was golden as honey. After the vegetarian lunch, my father sat before the altar and took out an old notebook —leather cover cracked, corners frayed. He said it was Grandmother’s notebook. Amid scattered notes —“buy soy sauce,” “dry sweet potatoes”— there was a page underlined:

“No one leaves alone. In life and in departure — remember the place of your promise.”

He closed the notebook, looked at us, and said:

—“When I took her to the city, I only thought of ‘what was convenient,’ so as not to trouble you. And there was nothing convenient: there was a price. Step back once to be kind, listen once to the silent —and everything settles.”

From then on, the strange things ceased. The cat no longer stared; the clock kept ticking. My father’s cough eased; color returned to his face. Each afternoon, he took the teapot to the starfruit tree, sitting in silence as if conversing with an old friend.

Once, I dreamed of Grandmother. Her gray hair was neatly tied, her hand smoothing fabric; on her fingertip glinted the bodhi bead. She said:

—“Do not be too quick to burn what has not spoken its last word. The living, learn to listen; when silence comes tomorrow, there will be less regret.”

I awoke; outside, the starfruit leaves brushed the eaves with a soft tac-tac. Suddenly I understood why the flames went out three times: not to frighten us, but to remind us of a promise —simple, yet heavier than iron, heavier than ashes.

The following year, on the first anniversary, we prepared her favorite vegetarian dishes: sour pumpkin soup, boiled greens with soy sauce, and a bowl of mung bean dessert with toasted sesame. When we lit the incense, the flame burned steady and warm.

My father clasped his hands, whispering:

—“Mama, stay here. This house, this starfruit orchard, we will tend them. To live in harmony, to die in peace —we’ve learned it now.”

In the yard, ripe starfruits fell with a soft plop. My mother looked and smiled:

—“Grandmother is giving them to the children.”

The grandchildren ran; with sticky hands and tart mouths, they laughed aloud. In their laughter, I thought I heard a faint sigh —a long, peaceful breath.

The altar flame burned steady and deep. And from then on, we no longer feared it might go out. Because we had learned how to keep the fire —with promises and with listening.

News

Dumating ang bilyonaryo nang walang paalam at nakita ang katulong kasama ang kanyang triplets — ikinagulat niya ang kanyang nakita/th

Galit na galit na umuwi si Benjamin Scott nang araw na iyon. Isang napakasamang araw sa opisina. Stress na kinakain…

KAKALABAS LANG NAMIN SA KORTE, IBINATO NG ASAWA KO ANG ISANG LUMANG, PUNIT-PUNIT NA BACKPACK SA MUKHA KO SA HARAP NG BIYENAN KO. PAGDATING KO SA BAHAY AT PAGBUBUKAS KO NITO, NAWALAN AKO NG MALAY SA IYAK…/th

Tumunog nang tuyo at mabigat ang martilyo ng hukom sa kahoy na mesa:“Ipinapahayag ng hukuman na sina Trần Anh Quốc…

NAGSINUNGALING ANG ASAWA KO NA MAY BUSINESS TRIP DAW—PERO HULI KO SILA NG KABET NIYA SA ERUPLANO./th

NAGSINUNGALING ANG ASAWA KO NA MAY BUSINESS TRIP DAW—PERO HULI KO SILA NG KABET NIYA SA ERUPLANO.HINDI AKO NAG-ISKANDALO—BULONG LANG…

Kakaalis pa lang ng asawa ko para sa isang business trip nang bumulong ang anim na taong gulang kong anak na babae nang may pag-aalala: “Nay… kailangan nating tumakbo palabas ng bahay. Ngayon na.” Taranta akong tumakbo kasama ang anak ko, at limang minuto matapos kaming makalabas ng gate, isang kakila-kilabot na trahedya ang nangyari sa Xóm Đông…/th

Dalawang oras pa lang ang nakakalipas mula nang umalis ang asawa ko nang hilahin ng anak ko ang laylayan ng…

Ako ay 65 taong gulang. Nagdiborsyo ako limang taon na ang nakararaan. Iniwan sa akin ng ex husband ko ang bank card na may 3,000 pesos. Hindi ko ito hinawakan. Pagkalipas ng limang taon, nang i-withdraw ko ang pera… Ako ay paralisado./th

Ako ay 65 taong gulang. At pagkatapos ng 37 taon ng pagsasama, iniwan ako ng lalaking halos buong buhay ko…

Pinatay ng Groom ang Bride sa Mismong Kasalan at ang Katotohanan sa Likod Nito…/th

Noong umagang iyon, ang Tân Phượng ay kasing sigla ng isang pagdiriwang. Sa daan patungo sa bahay ng groom, puno…

End of content

No more pages to load